In Pictures: Drawings from Prisons, Internment Camps and Gulags

The Drawing Center, in New York, presents a historically and formally diverse collection of works by incarcerated artists

The Drawing Center, in New York, presents a historically and formally diverse collection of works by incarcerated artists

Few Romantic notions have remained more pervasive in our collective consciousness than the idea that the human spirit cannot be caged. This is doubly reinforced when the body housing that human spirit is shackled inside a prison of some kind, helpfully literalizing an otherwise metaphoric flight of fancy. The Drawing Center’s historically and formally wide-ranging show, ‘The Pencil Is a Key: Drawings by Incarcerated Artists’, takes this faith in the unfettered soul, which can soar even in the most adverse conditions, as its spiritual through-line – for better and, at times, for worse.

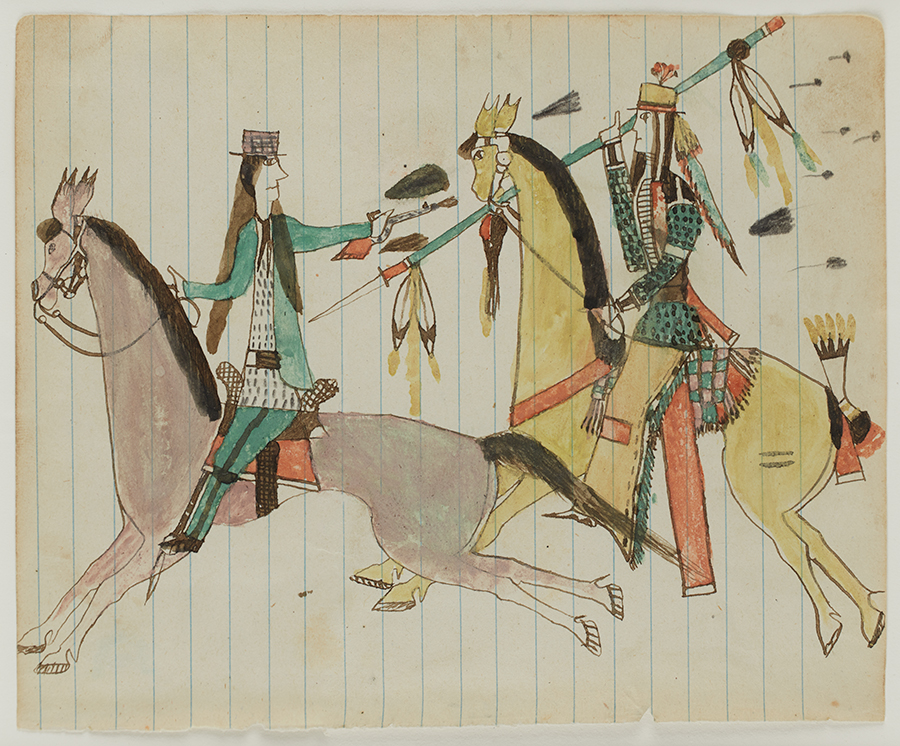

Organized in roughly chronological order, beginning with the 1789 French Revolution, the exhibition includes drawings by several household names, some relative unknowns and a clutch of ‘outsider’ artists. (Artworks by the incarcerated were, of course, one of Jean Dubuffet’s original categorizations for art brut.) While laudably well-intentioned, the curatorial decision to display the works according to instances of historical injustice seems, at times, restrictively conscientious and appears to have led to the inclusion of some weaker works in a bid to name check particular atrocities. The litany is long and bloody: the genocide and forced displacement of Native Americans; the Holocaust; the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II; Joseph Stalin’s Soviet-era Gulags; Apartheid in South Africa; Augusto Pinochet’s secret prisons in Chile; the US’s War on Drugs; Egypt’s post-Arab Spring crackdown; Syria’s civil war; the repressive Chinese surveillance state; Turkey’s ongoing assault on the Kurds.

The ambient thrum of human cruelty is inescapable but, true to the show’s intent, we do see the spirit take wing. Works by artists held in Nazi concentration camps – Halina Olomucki’s The Chimney (1939–42), for instance, which depicts a twisted pile of bodies awaiting incineration in two candle-like chimneys – exemplify our need to transmute horror into art. Alexey Wangenheim, Stalin’s loyal meteorologist who was nevertheless sent to a Gulag on trumped-up charges and summarily executed in 1937, spent his prison years drawing educational postcards featuring luminous solar eclipses and a spectral aurora borealis for his young daughter, thereby reaching out from his cage to touch not only his absent loved one, but the cosmos itself. Visionary outsiders like Welmon Sharlhorne, Frank Jones and the ubiquitous Martín Ramírez seem to have tunnelled their way into realms beyond our mode of knowing.

In a show filled with works that stand as elegant cries against history’s many horrors, however, one piece remains a nagging thorn in my side. It is The Kander Valley in the Bernese Oberland (1926) by the idiosyncratic world-maker and composer Adolf Wölfli, one of the most influential artists in the show. His work was a lodestone for the surrealists and was lionized by both Dubuffet and André Breton, who described it as ‘one of the three or four most important oeuvres of the 20th century’. And with good reason: Wölfli’s kaleidoscopic drawings, often adorned with unplayable musical notation and stocked with a menagerie of mysterious entities, are among the most beguiling in the ‘outsider’ canon. They were also produced by a predatory paedophile, who spent most of his life institutionalized for his crimes. As such, we might prefer these works to mark the point when the uncaged human spirit is banished, cast into a dark pit like the Lucifer of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). After all, Wölfli may have suffered from severe psychosis, but he also perpetrated some heinous acts. Yet, art cannot always be swept aside so easily. Sometimes, while it may not be irreproachable, it demands to be admired all the same.

‘The Pencil Is a Key: Drawings by Incarcerated Artists’ continues at the Drawing Center, New York, USA, until 5 January 2020.

Main image: Zehra Dogan, Fistan (Dress), 2018, marker pen on hand-sewn dress, 98 × 240 cm. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: Martin Parsekian