Post-Cyber Feminist International 2017

Twenty years after the First Cyberfeminist International at Documenta X, what does Cyberfeminism look like in 2017?

Twenty years after the First Cyberfeminist International at Documenta X, what does Cyberfeminism look like in 2017?

‘The future’s not what it used to be,’ said Eleanor Penny, opening the ‘What Can Post-Cyber Feminism Do For Reproductive Justice?’ panel at the 2017 Post-Cyber Feminist International, held recently at the ICA, London. Programmed by Xenofeminist Helen Hester of Laboria Cuboniks and curator Rosalie Doubal, it comes 20 years after the First Cyberfeminist International took place at Documenta X in Kassel, in 1997.

20 years is a long time in cyberspace; 2017’s International was blessed by the presence of some of the first conference’s participants including Cornelia Sollfrank, co-founder of the Old Boys Network, who mentioned her chagrin at being recently invited to appear as a ‘grandmother of Cyberfeminism’. ‘Even Cyberfeminists grow old,’ admitted Faith Wilding of Sub Rosa as she searched for her glasses. In the opening ‘N Hypotheses’ panel, Diana McCarty of FACES, netzkultur, net.art and nettime offered a detailed rundown on the First International’s influences (‘specific to European net culture of the ’90s … the new East-West dynamic within Europe … coming out of this twisted situation of post-Soviet space’) and practices (working with open-source software to ‘blur the line between user and developer’).

If that was Cyberfeminism, what might Post-Cyber Feminism be? This was #postcyberfem’s abiding question. It’s ‘not about being post-feminist,’ nor is the xeno in Xenofeminism anything to do with xenophobia – rather, Xenofeminism is about ‘productive alienation’ (Diann Bauer of Laboria Cuboniks). So what’s changed?

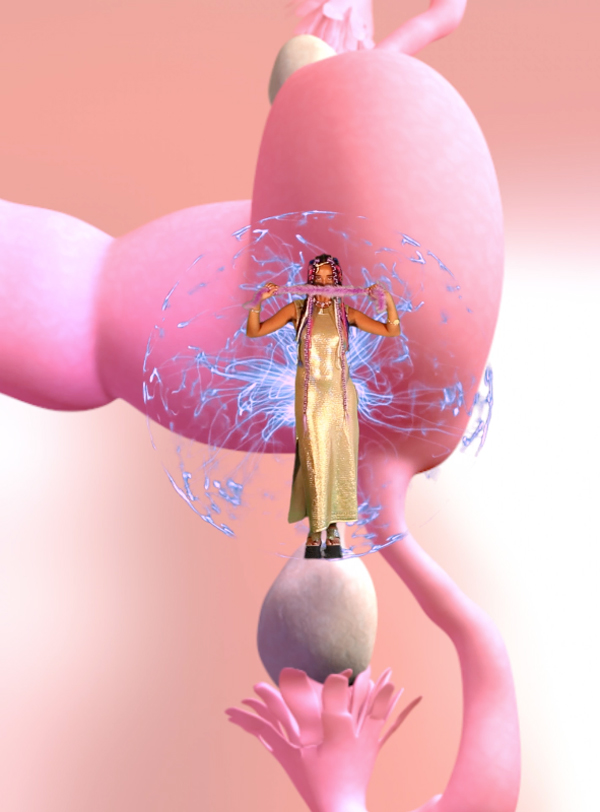

‘We make art with our cunt,’ wrote ’90s cyberfeminists, VNS Matrix. ‘Gender abolitionism’ (Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation, 2015) has marked a shift in rhetoric, and Cornelia Sollfrank was the only 2017 delegate I remember to use the c-word. ‘The womb should be deemed obsolete,’ said artist and filmmaker Shu Lea Cheang in the ‘What Can Post-Cyber Feminism Do For Reproductive Justice?’ panel, where biohacker Mary Maggic pointed up the ‘fuzzy biological sabotage’ of our already ‘biopolitically … colonized’ semi-human, non-binary bodies. Unapologetic ‘womb power’ (for example, Tabita Rezaire’s ‘radical self-love kit’ in her 2016 film Peaceful Warrior) came largely from BAME delegates. E. Jane’s musical persona MHYSA (‘she’s real because I put her on the internet’) celebrates ‘black femme’ identity. These two were part of a number of Friday night film screenings as part of ‘Glitch Shorts’ which were followed by a Glitch@Night music session by SCRAAATCH where, Legacy Russell said, ‘we’ll throw some moves,’ putting bodies at the heart of resistance.

Saturday’s ‘Black Feminism and Post-Cyber Feminism’ panel was euphorically purposeful, advocating ‘a decolonization of the mind’ and a pressing need to represent non-white experience online in ways that counter the stereotypes offered by traditional media, even as ‘capitalism [is] taking over these protest spaces’ (as Tamar Clarke-Brown mentioned at Friday's Glitch Shorts panel) with marketing companies appropriating black feminists’ creative labour.

Reflecting on the First Cyberfeminist International in 1997, Faith Wilding asked: ‘Where is the Feminism in Cyberfeminism?’ One might just as well ask: ‘Where is the cyber?’. The answer is is ‘post’, at least post the hopes of the ’90s: ‘Utopia in digital spaces… mostly it didn’t happen,’ said Akwugo Emejulu. Black feminists in particular talked about being AFK (Away From Keyboard): ‘You have to always be visible and productive or else you’re invisible,’ (Siana Bangura). As E. Jane whose ‘primary residence is cyberspace’ commented, ‘you can’t drink water and you can’t breathe air on the internet.’ Sollfrank described how the Old Boys Network began as a strategy for sharing Documenta’s artspace, with the offline organizational labour of social reproduction at its heart. Sollfrank’s primary question remains ‘Where are we?’ Diana McCarty advised practising an ‘invite your neighbours’ principle, designed to enable participation by everyone in your immediate meatspace. Wilding declared: ‘The most important thing is to turn up.’

Post-Cyber Feminist International provides few definitive answers, but raises urgent questions. Sara Ahmed’s persistently challenging Feminist Killjoy was frequently invoked (many of the attendees were associated with Goldsmiths, Ahmed’s former university). This is appropriate, as Post-Cyber Feminism’s ‘flat-hierarchical’ (Sollfrank) diversity fosters productive tensions, drawing on Sadie Plant’s definition of it as ‘an absolutely post-human insurrection’ in her landmark book which sees its 20th anniversary this year, Zeros and Ones (1997). The zeros in binary code, according to Sollfrank, disturb binaries, the Lacanian take that ‘whatever [woman] knows can only be described as not-knowledge,’ her examination of productive negatives in A la Recherche d’information Perdue echoing The First Cyberfeminist International’s 100 anti-theses's repeated ‘Cyberfeminism is not …’

‘You don’t have to nail something down in order to build something,’ said Victoria Sin at the ‘Diagramming Post-Cyber Feminism’ workshop convened by Res. – a mutable project based in a gallery and workspace in Deptford, South East London – perhaps invoking Audre Lorde’s ‘master’s tools,’ also referenced by Diana McCarty in the opening panel. And in case you’d like to know, yes, Cyberfeminists use Macs: even as they consider the possibilities of non-proprietary software, some of the master’s tools have to be employed. Legacy Russell’s ‘Glitch Feminism’, coined in 2013, seizes on ‘the causality of error,’ available in mainstream technology though, as Clarke-Brown pointed out, these practices are also available to Cyberfeminism’s antagonists: ‘Trump … acts through glitching.’ Just as offline oppressions have intensified in their online incarnations, so the fight against a reinforced ‘big daddy mainframe’ (VNS Matrix) has got harder. For Sollfrank ‘the solution is still micropolitics,’ though Hester calls for a response that tackles the politics of scale used by multinationals and government.

But is any of this art? Sollfrank, who regrets that much of the First International’s art wasn’t recorded, maintains the interdependency of activism and aesthetics: ‘Everything I did with Cyberfeminism was as an artist, I was interested in forms of organization as an aesthetic practice.’

The Post-Cyber Feminist International was held at the ICA, London 15 – 19 November 2017. Main image: Victoria Sin performing at Glitch @ Night, part of Post-Cyber Feminist International 2017, ICA, London. Courtesy: ICA, London; photograph: Mark Blower