Raymond Pettibon

New Museum, New York, USA

New Museum, New York, USA

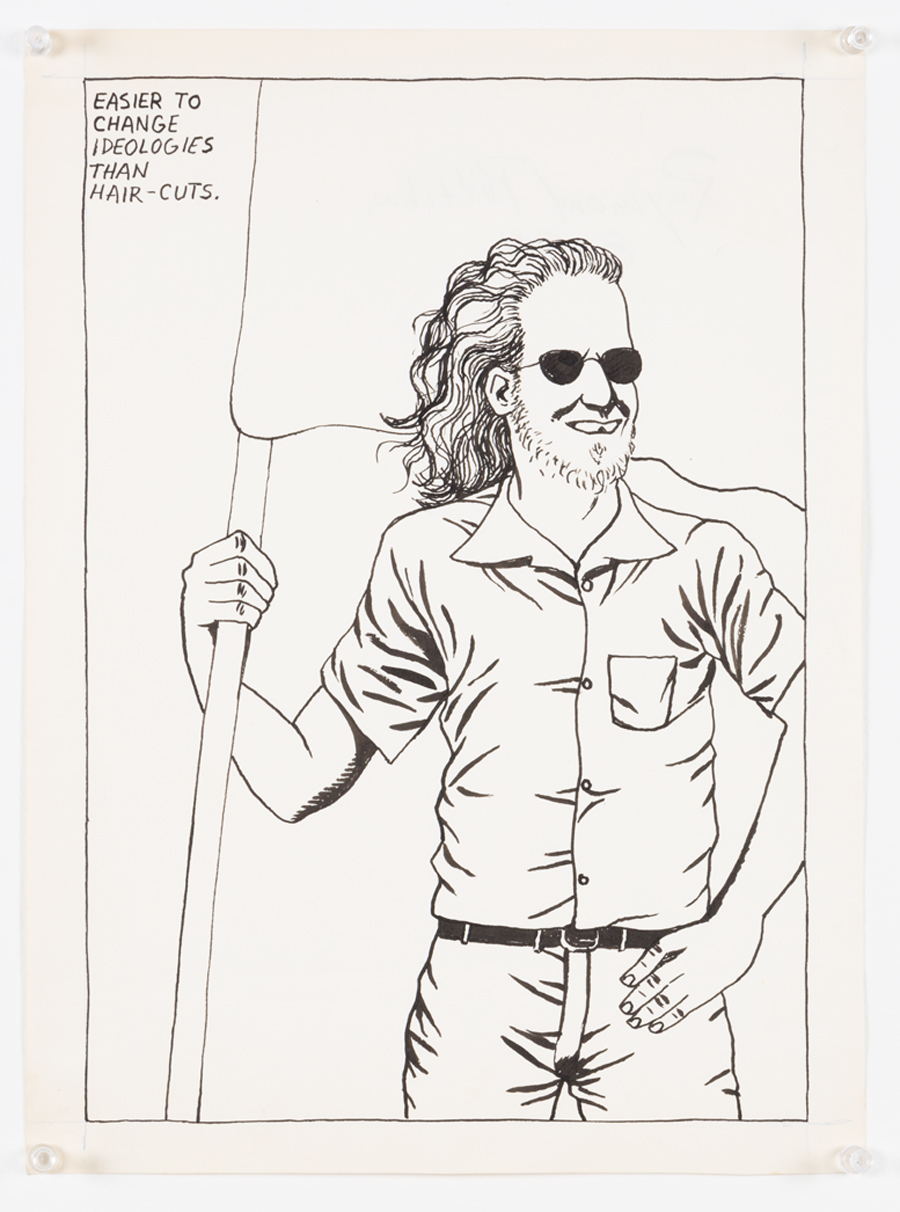

Raymond Pettibon, whose retrospective ‘A Pen of All Work’ recently opened at the New Museum, is an artist of an almost apocryphal reputation – which isn’t to say that he’s not real, but that his reality feels anecdotal, provisional, rumoured, overheard, inaccurate, remembered in the marginalia. Who – and what – is he? California’s Goya, zine legend, unsung novelist, anti-hero. A story I once heard: Pettibon was afraid of friends and family stealing his drawings from his studio, so he taped them to the ceiling. All these papers, fluttering overhead. Another: the poet Kevin Killian once pointed out to me that the likeness of his partner, the writer Dodie Bellamy, who has collaborated with Pettibon in the past, seems to keep showing up as a member of the Manson Family in the artist’s drawings of the murderous cult leader and his followers. (Bellamy was a member of a cult once: see her 2014 book The TV Sutras.) In Pettibon, you see yourself and the politics that make that self up.

In this new retrospective, that self first appears in words painted onto walls. Images come next: a stretched, Joan Crawford-esque face, for example, above which Pettibon has written: ‘HER MANNER WAS SO EASY, SO ARTLESS AND PLEASING HE COULD NOT BELIEVE IT AN ACT, THOUGH SHE PERFORMED IT WELL’. She is he, really, and it’s an act – a dance of and for the pantheon: one in which Pettibon does the voices, the police and the policed, in fragments and among ruins.

Across three floors, as well as the museum lobby, ‘A Pen of All Work’ provides a sketchy, synecdochal overview of Pettibon’s cluttered, catch-all practice rather than a complete picture of what he’s produced thus far. The roughly 900 drawings, paintings and films displayed represent less than five percent of his known output – and this excludes the untallied stolen or lost drawings, some of which have floated less reputably onto the market. With this futility baked-in, ‘A Pen of All Work’ selects, arrays and highlights Pettibon’s usual themes in order to provoke the viewer into a kind of historical timewarp: from the slouching-toward-Berkeley teenage malaise of the 1960s (in work made in the 1980s), to the Bush-Obama wars that brought us Donald Trump. In between, drawings sequence the DNA of US culture and counterculture, from Pettibon’s postwar childhood drawings of airplanes and Nazi surfers (who also cameo in his excellent 1989 film, Sir Drone) to his rendering of the painting commonly known as ‘Whistler’s Mother’ (1871) – an art-historical translation that recalls, for me, Francis Bacon’s stark 1953 re-imagination of Diego Velázquez’s Pope Innocent X (1650).

Pettibon’s drawings, zines and films are primarily interested in history and its actors (both big and small), bringing into focus their often-malevolent agenda and all-consuming rage. Likewise, his work, particularly in the interrelation between image and text, continuously challenges the way state-sanctioned narratives of power and resistance enforce our sing-song agreement with law and order, fashion and fascism. In Pettibon’s work, Americans are dumb and trigger-happy: believers and con-artists who fuck, consume and dance in ignorance and fealty to false idols, such as preachers, parents and political parties. And while homoerotic baseball players, presidents, Elvis, Manson, Batman and so on (like the artist, I keep making lists) dominate Pettibon’s heaven of lesser gods and greater demons, it’s our implication in this vulgar chaos of competing voices that the artist identifies as singularly – and literally – disturbing. Or, as Pettibon puts it in No Title (We Do Not) (2011), a drawing based on a photograph of the executed Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini, hung by the ankles from a bridge: ‘WE DO NOT KNOW THE PAST. WE READ HISTORY AS ITS LAID OUT CHRONOLOGICALLY, ANESTHETIZED ON THE TABLE. WHAT WE KNOW WE KNOW BY RIPPLES AND SPIRALS EDDYING OUT FROM US IN OUR OWN TIME.’

The waters of history crest most dramatically in Pettibon’s large and gorgeous drawings of waves, which appear in the New Museum in a dedicated, Instagram-friendly room. Often in these large works, which are among the artist’s most sensuous and painterly, a surfer rides a big swell, with typical, oracular statements written above or below. From the early 1990s until the 2000s, these drawings were much wordier, with capitalized statements about ‘NATURE’, ‘MOTHER OCEAN’ or ‘THE MORAL WORLD’, though these have generally evolved – but not uniformly – into sparer sentences in a lowercase cursive. In No Title (As to Me) (2015): ‘As to me I could do no farther good after quitting my friend the sea. / Someday you may find yourself / at sea alone. / The sand and water to which / we are reducible are as a / rock to me.’

Most of the dialogue of Kathryn Bigelow’s 1991 film Point Break could have been written by Pettibon: it has more or less the same view of history. As Bodhi, the leader of a gang of bank-robbing surfers and the film’s charismatic antihero, says: ‘This was never about the money: this was about us against the system [...] that kills the human spirit. We stand for something. We are here to show those guys that are inching their way on the freeways in their metal coffins that the human spirit is still alive.’ Pettibon might revise Bodhi’s optimistic view slightly, arguing that history and its system live on, while the querulous human spirit has died, and that Bodhi – violent and stupid, like many of the artist’s protagonists – is all the proof we need. For Pettibon, it may be us against the system but, more importantly, it’s us as the system, fighting each other and ourselves to the soul-death of comic-book America, often without any discernible motive other than violence for violence’s sake. In Point Break, Bodhi is ultimately killed by a wave, after eluding an improbably handsome and witless FBI agent, played by Keanu Reeves. In Pettibon’s work, the wave of history is the wave of Bodhi-ism, further evinced by our presidents (a favourite subject of the artist), the worst of which seems to have finally arrived (though the artist might disagree on that point). Necessarily, at this critical juncture in US life, ‘A Pen of All Works’ asks us to consider Pettibon’s politics – both electoral and philosophical – as much as we do his drawings. Within that field, Pettibon reminds us, with knowing futility, to think again before we wax our boards.

Main image: Raymond Pettibon, Captive Chains, 1978, artist’s book, 27 x 19 cm. Courtesy: David Zwirner, New York