Robert Ashley’s ‘Improvement (Don Leaves Linda)’ Returns to the Stage

This opera wants to know whether memory is scientific or occult. It answers the question by rejecting it.

This opera wants to know whether memory is scientific or occult. It answers the question by rejecting it.

It is hard to believe that Improvement (Don Leaves Linda) (written in 1985 and first performed in 1991) – the first opera in Robert Ashley’s Now Eleanor’s Idea tetralogy – was not initially written for performance. But in its recent run at The Kitchen in New York, Gelsey Bell’s Linda is astonishingly moving; re-listening to the 1992 Nonesuch recording, for which Jacqueline Humbert developed and performed the original role, I find myself missing Bell’s facial expressions. Her eyebrows do as much as an Ashley monolog does with a few notes of a minor scale in the same range.

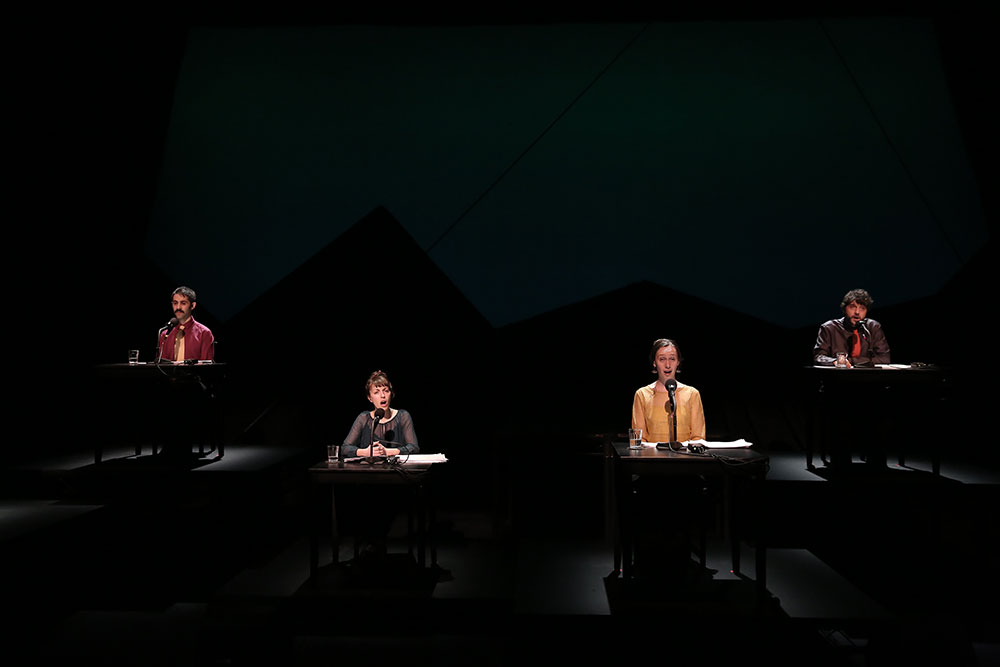

The opera opens with Don (Brian McCorkle) leaving his wife, Linda, while she’s in the bathroom at a roadside turnoff. Temporarily named Carlo, he arrives alone at the Airline Ticket Counter, where Bell, as Linda, plays the Agent, Carla. As she asks him about his absent wife, his answers precede her questions, sonically supporting Linda’s narrative claim to inevitability. When Linda rides back to the airport, carpooling with The Unimportant Family, the interrogation is reversed, and she delivers ‘The Indifference Speech’ (scene six); she is not angry or upset, she calmly intones, because things had to happen this way. Her appearance of complacency is sufficient, she argues, for most to assume there’s a corresponding internal indifference. Throughout the 90-minute performance – which takes Linda to a new lover (Mr. Payne, also McCorkle), a new city, a party, older age and a final world-historic game of bridge – the restrained gestures and harmonies of the (fantastic) cast of six maintain this tension between apparent complacency and real spiritual upset. They sit at separate desks, singing or speaking or muttering in a restrained range, in front of a shadow of hills or pyramids and in the glow of a continual sunset, the light of which changes colour as they move through the stages of Linda’s self-discovery.

In the programme notes, music director Tom Hamilton describes how the technical and performative constraints necessary to develop the electronic orchestra’s precise sparseness made live production seem unfeasible. Ashley’s arrangement was a minimal guide for the singers’ impossible delivery of his wordy libretto. This meant that when they did decide, after all, to stage it, they had not prepared to separate out the vocal tracks – the original singers had to keep perfect time with their own recorded voices. Hamilton has since recreated the orchestration, limiting ‘the tonal palette to what [they] had available at the time’ and giving the performers more breathing room.

There is something nostalgic in Improvement, and it’s not the 1980s synthesizers. Perhaps it is contemporary opera’s own nostalgia for a form that strove to represent a universal; the titular divorce is meant to allegorize Jewish migration from the 1492 Alhambra Decree to the diasporic 1940s US west coast. Improvement is an opera about memory: in the ninth scene, ‘The Contents of Her Purse’, Mr. Payne – a tap-dancer ‘who remembers everything’ – suggests a mnemonic game of seduction, in which he gets a kiss for every item in her purse he remembers correctly. She’s afraid, until she realizes that the contents will have changed since he memorized them; he’s betting kisses ‘on the past recaptured.’ When Linda reports George’s speech, they sing in unison, suggesting that we can access his voice by way of her memory. He explains that ‘to know every fact of golf in the experience of playing it’ also lets the knower understand ‘how people beget people’, how cars work and what’s in her purse.

Here, Linda is quoting Payne’s allusion to Frances Yates’s The Art of Memory (1966), a ground-breaking recovery of the Greek tradition of mnemotechnics, the title of which appears on Ashley’s extended cast list. The technique, which involves spatializing mental images across predetermined ‘loci’, is more likely to be recognized, now, from the BBC’s Sherlock (2010-2017) than from Yates’s research. But this opera sets out to develop a related technology of images, plot and sound that, arranged precisely enough, could contain a broader historical experience. The list of characters also identifies Payne with Giordano Bruno, the 16th century friar, scientist and philosopher who was allegedly called by the King to explain whether his art of memory was scientific or magic (and later killed by inquisitors for heresy). Like Bruno’s inquisitors, Improvement wants to know whether memory is scientific or occult. The opera answers the question by rejecting it, and instead creates a technical system for recording, at once, historical, spiritual and individual experience.

Main Image: Robert Ashley, Improvement (Don Leaves Linda), 2019 performance. Courtesy: The Kitchen; photograph: © Al Foote III