Sarah Sze and the Rhetorical Power of Fire

In a new show, Sze pairs precision with nods to disassembly or messy composition

In a new show, Sze pairs precision with nods to disassembly or messy composition

According to the print-out of Sarah Sze’s personal calendar – on crumpled paper, taped to the wall near hanging scissors, a tape measurer, and some scrawled outlines of wolves – the artist planned to make ‘all video decisions’ for her solo exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar on 12 August. Over the next two days, she instructs herself to ‘Finish Sculpture’. If you follow this breadcrumb trail of materials into the next room, you’ll find an installation that refuses to be finalized.

In this way, the eponymous show is cumulative; as you walk toward Crescent (Timekeeper) (all works 2019), a central sculpture-cum-projection, you pass a package for a 64GB SanDisk memory card, affixed with a thumbtack to the overlapping edges of images – one shows a white fox in motion, another an eddy – printed in muted blue on paper, with a scrap pinned lengthwise across the top. A changing, projected image glides across the surface of these papers, occasionally passing over its own likeness (among my favourite details in this show are the moving animals, in miniature, projected over still prints of themselves – as if Muybridge documented a wolf’s existential crisis). Instructions appear with pencilled-in frames from ‘missing’ pieces, like the phrase ‘Manhattan Mini Storage receipt’ written in pencil.

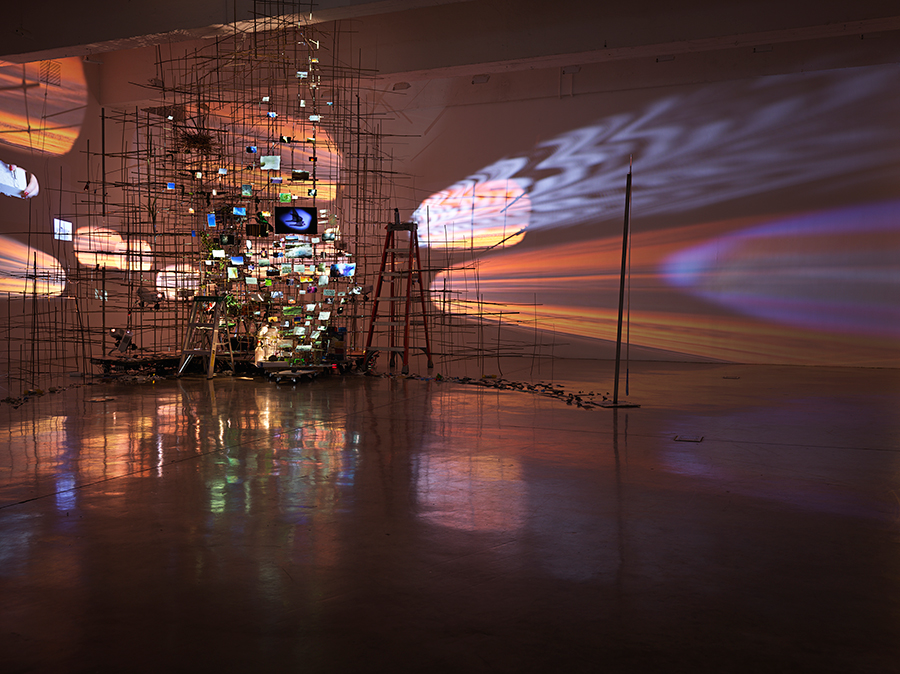

In Crescent (Timekeeper), a stack of projectors, rotating on wood supports, casts films across the walls, a sort of sundial where the full rotation measures minutes rather than days. A steel lattice rises as scaffolding around a ladder, giving the impression of a work in progress. But there’s nothing unfinished here; this is a representation of an unfinished state, rather than rawness itself. Sze pairs flourishes of precision with nods to disassembly or messy composition. In Crescent, for example, an assortment of prints with rough edges are suspended from the central structure, arranged such that each becomes a screen with the same dimensions of the small rectangle of light it captures (e.g. videos of flame or water). This process recurs upstairs in Images in Translation, this time with a desk in disorder, showing the projected mini-videos on the desktop computer.

The press release describes Cresent (Timekeeper) as ‘a Plato’s cave of imagery,’ implying that Sze offers some all-seeing philosopher’s perspective over and against the viewer’s more limited encounter with shadows. It makes formal sense – the allegory, after all, is about the dangers of only seeing what has been projected – but if the show is meant as a critique of empiricism, it is a rather materialist one. Perhaps the reference is not to the limits of the senses, but to the rhetorical power of fire.

Fire is a recurring motif: a torn image of a flame appears in the centre of Ghost Print (Dark Violet) and Blue Tumble (After Studio), two smaller-scale (40.6 × 50.8 × 3 cm.) paintings displayed in a replica of an artist’s studio in the back room, and again in the strikingly bright Last Glimpse (After Object), a larger painting upstairs. This work is part of a triptych that layers oil and acrylic paint with collaged prints and fabric to create a what looks like the aftermath of a rather pretty explosion. The effect is emphasized by After Object, a floor sculpture comprising lines of white paint splatter that emerge from a clear, semi-circular blank blast area around Last Glimpse. While most of the elements of these painting-sculptures are layered or blended into new forms, the print of a small fire is loosely attached to the centre with a single piece of tape.

Sze’s work is often described by way of seemingly contradictory states of ‘suspension’ or ‘collapse’; she freezes process to collapse it into lingering structure. Sze’s idealism is that of the unadorned ladder, standing in the middle of Crescent (Timekeeper). The ladder – at once a symbol of ascendance (Miró, O’Keeffe) and an anti-symbolic reference to art’s installation – gets to have it both ways.

‘Sarah Sze’ continues at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA, through 19 October 2019.