Space, Speed, Stasis

A series of installations and a new LP from artist, composer and percussionist Eli Keszler

A series of installations and a new LP from artist, composer and percussionist Eli Keszler

In the spring of 2016, Eli Keszler, a 31-year-old artist and composer whose work envisions architecture as instrument, was invited, along with the artist James Hoff, to assemble a collaborative sound installation at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts: the only building in the US designed by Le Corbusier (completed IN1963). Keszler arrived ahead of Hoff to tour the space and, as he walked around with the gallery manager, he noticed that the ceiling was pocked with eleven, apparently uniform holes. ‘I kept looking at them,’ Keszler explained to me, ‘and I thought they seemed a lot like intercom speakers. I asked the gallery manager about them but she wasn’t aware of any internal speaker system.’ By examining photos of the Center’s exhibitions from the 1970s, Keszler was able to determine that they were, indeed, speakers. He located the wiring and followed it back to a wall in an administrator’s office. With permission, the building’s supervisor tore the wall open to reveal an amplifier connected to an 11-channel stereo system. Incredibly, it still worked.

This is the kind of discovery that comes to light in the interplay of the macro and micro in Keszler’s interdisciplinary work. ‘I always examine the infrastructure of the spaces I’m working in,’ he tells me, ‘the piping, the lighting, the heating system: all of it.’ He describes his recent commissions, including Northern Stair Projection, his installation and performance at Boston’s brutalist City Hall in November 2016, in which he used electric transducers and wiring to send sounds from the boiler room in the basement to the nine floors above it.

Piano wire is another material commonly used by Keszler to bring out the ‘voice’ of large-scale structures. In Archway (2013), for instance, Keszler threaded piano wires from the Brooklyn side of the Manhattan Bridge down to the large archway on the cobblestone street below, where they formed a compelling lattice that terminated in large wooden panels. Attached to them were mechanized and amplified beaters that struck the wires to emit roars of vibration at one end, while trains and cars reverberated them from the other.

As Keszler often does in his installations, he performed a percussive work on a drum kit under the yawning wires. Watching him play can be hypnotic: he whirls around the kit, stopping only to bow a crotale – a tuned bronze offspring of the cymbal and bell. Human performance and architecture combine to produce sounds akin to animals bleating at an oncoming storm.

‘Drawing is a psychological process for me,’ Keszler explains. ‘I can see emotion in my marks: when I’ve been relaxed or nervous.’

This style of performance is largely absent on Last Signs of Speed (2016) – Keszler’s first full-length LP in four years and the debut release from Empty Editions, a label initiated by the Hong Kong-based Empty Gallery. With this record, Keszler foregoes the abrasive territory of previous work, for what he describes as ‘velvety’ textures: soft, melodic, sensual – adjectives not easily achievable on an album composed primarily with percussive instrumentation. It’s also Keszler’s most concentrated release to date, a result of him rediscovering the art of recorded composition. ‘I wanted to treat the recording as a self-contained environment,’ he says. ‘From watching people listen to music on the subway or on the street, I noticed how we lose ourselves in recordings in a very particular way – public space becomes private space. I’m interested in whether this could form a kind of grammar or syntactical logic.’

Inspiration did come from a physical space, if an unlikely one. ‘When I toured in Europe, I’d occasionally play in clubs that were equipped with beautiful sound systems. Their sound engineers would amplify my drums to extreme levels, especially the bass drum, which would transform into this voluminous, low-end, heavy object – like what you’d hear in dub. I welcomed the environments these sound systems created and let it shift my music into an entirely new direction.’

The melodious contra notes of the bass drum most strikingly highlight Last Signs of Speed’s nod to dub music and dance halls. They bound around the album, like large buoyant orbs, with Keszler counterpointing with quietly flurrying stickwork upon muted drums and glockenspiels. Accompanying him at a much slower velocity are sounds contributed by the String Orchestra of Brooklyn, the cellist Leila Bordreuil and the sound-sculptor Geoff Mullen. Auxiliary hints from a Fender Rhodes electric piano, a Mellotron and a celeste further colour the album. The resulting organic orchestration isn’t unlike the soundscapes crafted by avant-electronic artists that night clubs have increasingly been open to showcasing.

Along with space, the record highlights another of Keszler’s preoccupations:time. Were his frenetic drumming removed, the record would exist in a state closer to inertia than momentum. Different notions of time are evident throughout both Keszler’s music and his visual work – his graphic scores and drafted work. As he makes clear: ‘I’m drawn toward movement that is occurring at both hyper speed and almost static slowness.’

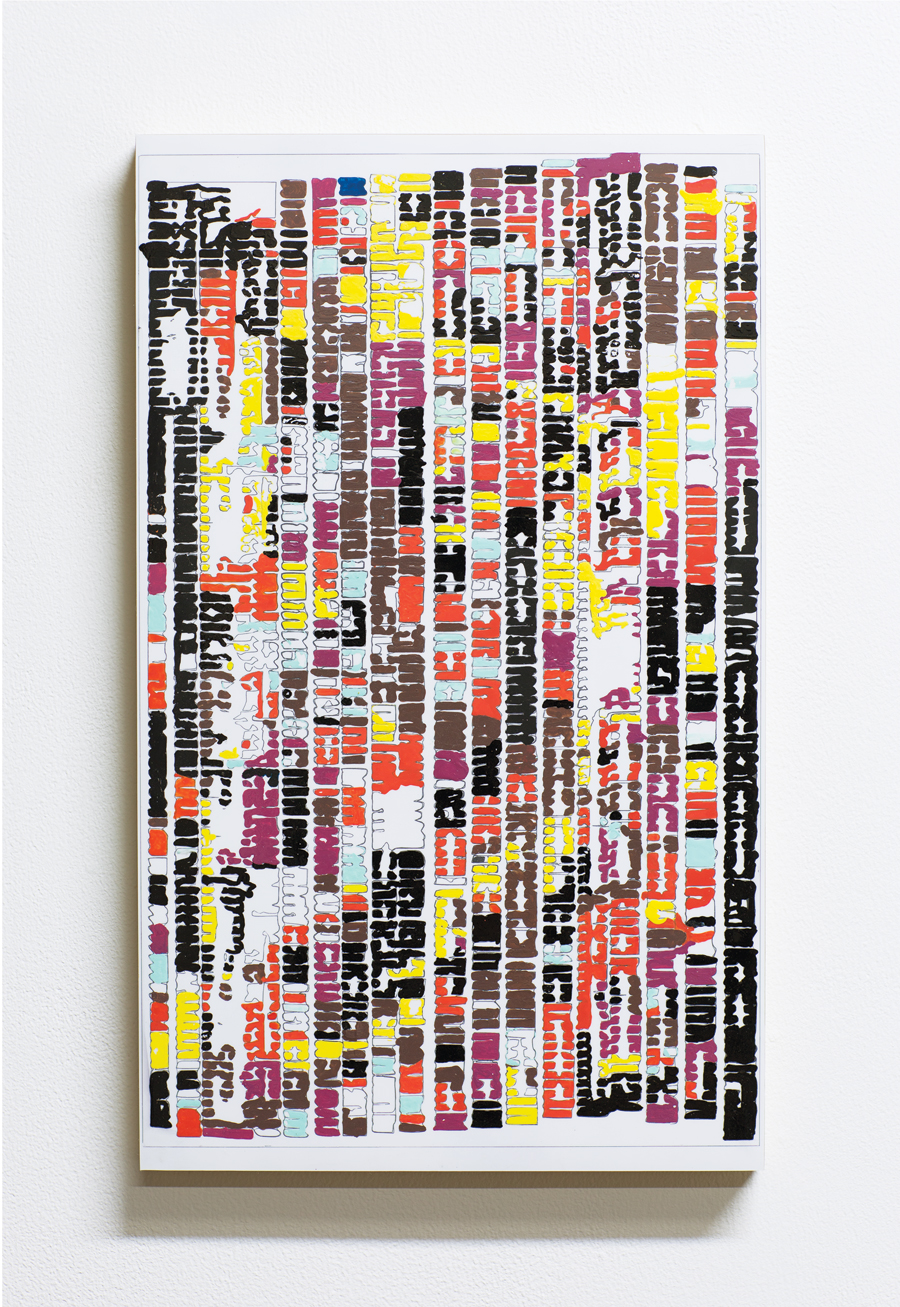

It’s not hard to see Keszler’s drawings as moments of visualized time. From far away they appear to depict geometric shapes yet, up close, these objects (such as the one used for Last Signs of Speed’s cover) are reduced to thousands of tiny, filamentary lines. To make them, Keszler engages in a meditative process of marking concentrated areas with a pen over extended periods. ‘It’s a psychological process for me,’ he explains. ‘I can see emotion in my marks, like when I’ve been relaxed or nervous.’ His scores forgo method for concept, corroding musical diagrams with chemically reactive material (Oxidized Score, 2016) or censoring the abstract typography in which they are written with large black strips (Railsback Curve, 2016); these act as a kind of guide to the performative aspect of Keszler’s compositions.

That there are so many components to Keszler’s work is an indication of his eerie mindfulness for detail. He describes being delighted by the sounds of London – birds, trains, cars – that were captured during a rooftop performance for the British radio station NTS. Keszler remains indefatigabile. Last month, following a tour of Asia, he and musician David Grubbs released One and One Less, a record of spoken word and sound derived from a piece the two performed – alongside a joint installation of Keszler’s sound boxes and Grubb’s poetic wall texts – at MIT’s List Visual Arts Center in 2014. Later this year, Keszler plans to show a series of new and recent visual scores and drawings at 67 Ludlow in New York.

‘The drawing projects and compositional work exist at a micro level,’ he declares. ‘The installations are the macro, but whether you break down the macro or build upon the micro, you’re creating narration, and I want to bring this sense of narration to my projects.’ In many regards, he’s already succeeded.

Main image: Eli Keszler, Oxidized Score, 2016. Courtesy: the artist.