Sub Titles: How Film Publications are Embracing the Shift in Print

Against a growing digital landscape, cinema magazines dedicated to print are on the rise

Against a growing digital landscape, cinema magazines dedicated to print are on the rise

Is film criticism in crisis? Is print dead? The answers depend on where you look. Legacy outlets are struggling to adapt to the digital landscape and virtually nobody can make a living as a film critic any longer. But, on the margins, the horizon looks bright. Over the last five years, alongside the revival of vinyl LPs, handsomely designed print magazines have popped up like paper mushrooms after a digital rainstorm. They hew to the specific: Four & Sons is about dogs; Perdiz is about happiness. In this new embrace of old media, cinema hasn’t been left behind. A spate of small publications exploring the far reaches of film culture has appeared, adopting a tight focus and an intimate format, often similar to that of a paperback book. Eschewing advertisements, they leave behind any concern with the new release schedule or the taste of general audiences, bucking criticism’s usual temporality and mode of address to stake out a different relationship between cinema, writing and reading.

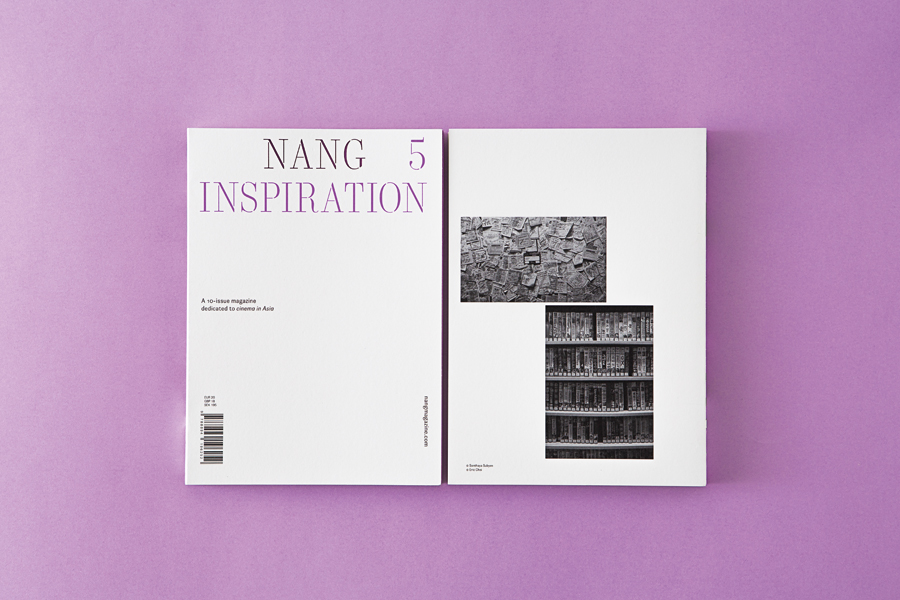

NANG, for instance, describes itself as ‘a ten-issue magazine devoted to cinema in Asia’, and takes its title from the Thai word for film. With a laser-cut cover and Swiss binding, its biannual issues boast themes such as ‘Inspiration’ and ‘Scars and Death’. Each volume of Fireflies is a diptych with two covers, dedicated to two directors, generally of utmost renown within cinephile circles but lesser known outside them, such as Alain Guiraudie and Albert Serra. Fiction, poetry and visual art by contributors including Wayne Koestenbaum and CAConrad sit alongside critical essays and interviews. Another Gaze offers feminist perspectives, striking a tonal balance between avoiding academic jargon and welcoming footnotes referencing scholars like bell hooks and Kathleen Stewart. The Swedish-language Walden focuses on experimental cinema, while Found Footage tackles the reuse of images in a bilingual Spanish/English edition. Despite the differences between these initiatives, all are independent ventures with uncompromising editorial vision. They are led by a passion for films – and for ways of responding to them – that are undervalued by the critical mainstream: an entity that is, it must be said, far more conservative, male-dominated and averse to ‘difficulty’ than its counterpart in contemporary art. These new publications embrace the generative possibilities of limitation, finding freedom in their niche remits and restricted circulation.

The idea of the ‘little magazine’ as a non-commercial enterprise devoted to championing overlooked practices is, in the main, associated with literature, where it has played a central, arguably indispensable, role in the emergence and diffusion of modernism. Yet, as a venue for criticism, the format is also central to the history of cinema, particularly within the avant-garde – an interest in which, loosely conceived, unites the new wave of magazines. In the postwar era, publications such as the New York-based Film Culture, founded by brothers Adolfas and Jonas Mekas in 1954, were instrumental not only in supporting emerging forms of filmmaking, but also in imagining new ways of writing about cinema. In the inaugural 1967 issue of CINIM, the first magazine of the London Film-makers’ Co-operative, Philip Crick positioned the publication’s goals directly in opposition to the sclerosis of the mainstream: ‘We aim to go beyond the thought-barriers of the cultural glossies […] CINIM means to become the astronaut of film critique.’ In his 1970 editorial for the second issue of Afterimage, Simon Field echoes that sentiment, writing: ‘We feel that there is little value in a magazine which reflects generally accepted tastes.’ Risk-taking cinema needs risk-taking writing but doesn’t always get it.

Plus ça change, apparently. The frustration with mainstream outlets has not waned; if anything, it has intensified. The glossies remain wedded to a general address, while the internet too often transforms writing into ‘content’ – with clickbait, listicles and hot takes proliferating in real time – putting pressure on critics to write short and fast. The new cohort inherits the non-conformist ethos of CINIM and Afterimage, serving as a refuge for alternative cinemas and alternative forms of criticism – for the personal, strange, forgotten and experimental. On their pages, the fringe becomes the centre. But they also reformulate the mandate of their predecessors in response to the exigencies of the digital age. The imperative to break with established critical conventions and popular taste remains, but now it is accompanied by a second rejection: namely, a withdrawal from the internet as a distribution channel.

The emergence of online platforms has undoubtedly served to democratize and diversify film criticism, and to catalyze new forms of cinephilia. These new magazines are the children of this transformation: they benefit from the atrophy of gatekeeping, make use of the internet as a means of promotion and some post selected articles online. Their editors – digital natives, all of them – have never known a cinema that was only gigantic and photochemical, a criticism that was only on paper. Yet, simultaneously, what unites them is a collective commitment to print, against convenience and cost. Contesting how film criticism circulates online, they are wilfully untimely and obstinately material, demanding to be held in the hand and kept on a shelf. They are made to endure. They slow everything down. Working from the assumption that a publication’s form shapes its content and its reception, they extract film criticism from the endless scrolling and linking of a web browser to create a frame for more attentive, careful encounters.

When describing his decision to adopt a print-only format for Little Joe – a publication devoted to the history of queer cinema that he founded, ahead of the curve, in 2010 – editor Sam Ashby spoke of wanting ‘the act of reading and touching and smelling the publication to be a moment of discovery for the reader’. The erotics of cinephilia meets the erotics of bibliophilia in a gesture befitting a project devoted to desire, subculture and remembrance. For Annabel Brady-Brown and Giovanni Marchini Camia, co-editors of Fireflies, hard copy is a ‘gesture of respect towards the films and texts’. An ungenerous appraisal would see such investment in the skilfully designed – and accordingly priced – object as elitist and precious, when the accessibility and quality of writing is what should matter. These editors, on the contrary, insist on materiality as a means of imparting an experience to the writer and reader that breaks with everyday norms and amplifies appreciation. And, besides, what’s wrong with a beautiful book?

After five exquisite issues, Little Joe went on hiatus in 2015. The production of these titles is done without much – if any – remuneration for those involved, and the question of sustainability looms large. The history of little magazines, in cinema and beyond, is a history of irregular publication and projects as short-lived as they are much-loved. But isn’t this part of their charm and urgency? In declaring from the start its end after ten issues, NANG seems to suggest so. This new wave will surely pass and, perhaps, before long – but maybe that’s okay. Others will fill the void. Print has the virtue of sticking around and the atemporality of these magazines means that their address to the future is as strong as their address to the present. Websites disappear and glossies often get thrown away, but I still have a stack of issues of Afterimage on my desk right now.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 203 with the headline ‘Sub Titles’

Main image: cover of Little Joe, no. 5, 2015. Courtesy: Little Joe, London