Tangled Up in Robert Morris (1931–2018)

The artist’s sculpture possessed an almost surreal promise, as if at any moment it might become a Really Living Thing

The artist’s sculpture possessed an almost surreal promise, as if at any moment it might become a Really Living Thing

I saw my first Robert Morris sculpture eight years ago, around the time I moved to New York. I had recently finished with school and the city was already upending my life. I didn’t know who I was or who I wanted to be. Every object and surface, face and friendship trembled with possibility. Contact with anything or anyone threatened to utterly transform me. This was worrisome. How could I change if I didn’t quite know myself? The Morris sculpture – pinned to a wall in a stranger’s apartment in Chelsea – was grey, velvety, untitled, its date unknown to me; it hung alongside other huge, expensive sculptures and paintings, mostly by artists whose names I recognized from museums. This was not a home where I had ever expected to have dinner, but a friend of a friend was house sitting, so I was invited over for noodles.

The house-sitter was a famous writer. He embodied, for me, everything about New York: its fleer of intelligence and wit, its world-weariness, its disdain for downtime and slow talk. And its bigness. I shook in his presence. If everything had as yet offered only its fearsome metamorphotic potential, then here, in this writer, was my Ovid – a magic hand to conjure the changes. It seemed that even his passing glance might render me a tree. Or a writer. Or an artist. Anyone. The choice was his. He roared with ideas, musings, asides. He regaled us with news of the world outside Manhattan, with stories from his recent travels – to Asia and Europe, two continents I had never set foot upon. He knew them well. Before New York, I had lived much of my life in South Carolina, a small state in the southern US, and an unambiguous nowhere, by my esteem.

The writer was on assignment, he told us. He had been tasked with writing about an artist who was soon to have a major retrospective at a great museum in an important city. Maybe it was New York. Maybe it was London. Maybe even Paris. He didn’t say so, but the fee he had secured for the job was a skyscraper-high pile of cash, the can-you-believe-it dollar-amount only whispered about in the city since no one, not anyone anywhere, had ever been paid so much to write about an artist. (Or so my friend whispered to me when the writer slipped into the toilet.) I liked him, but only in the way his large personality seemed to call for: as a character, as a person who had re-invented himself countless times into a figure not for the city’s present, but for its history. He was comic in the old sense of the word. A reveller, or revelator.

Papers, notebooks and catalogues were strewn about the floor, forming around him a bookish pentagram from which he convoked the spirit of Great Literature. I was mostly silent while we waited for our takeout to arrive until finally, at a lull in the writer’s monologue, I ventured to ask: ‘What’s that?’ I nodded toward the Morris behind him, its crumpled, soft form looking, to me, like a deflated balloon.

‘That? A Robert Morris,’ he said.

My friend interrupted, ‘You don’t know his work?’ He looked surprised, even embarrassed.

I grew red in the face. Perhaps now the transformative glance would come, and its effect would be a chilling one – poof, and I would devolve into a mess of limbs like that Morris: broken down, useless. Dispatched and then hung dead on a wall, a warning-sign to fellow fools.

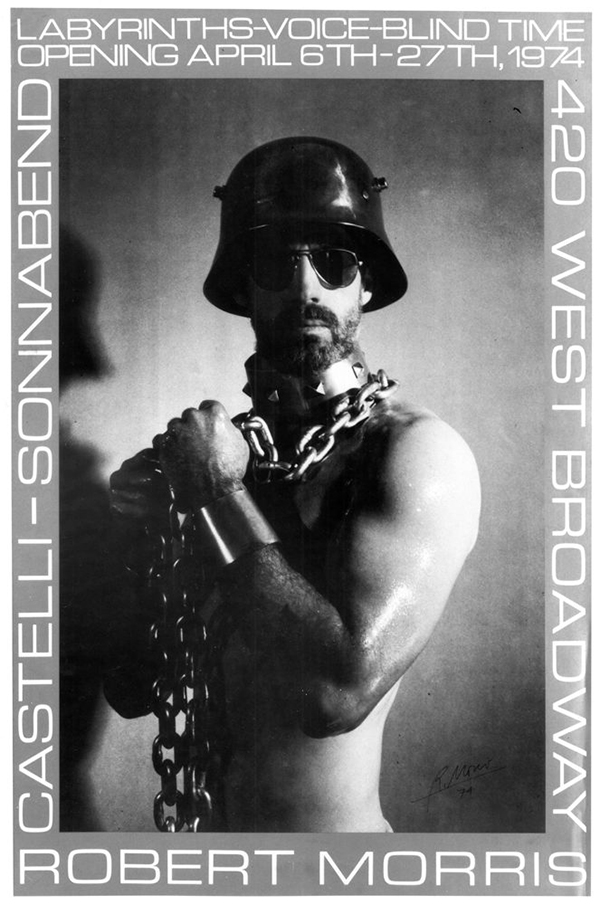

‘It’s one of his “tangles”,’ the writer explained. His tone was surprisingly understanding, more so than my friend’s. ‘You’ve probably seen his work. You just didn’t realize.’ He removed his phone from his pocket and called up the 1974 advertisement for Morris’s show at the Castelli-Sonnabend gallery. It shows the artist in an old army hat, his eyes shielded from the camera by huge aviator sunglasses. He’s shirtless, and he holds the leash of a chain bolted around his neck. The sweat of his left arm catches the light; it’s huge and muscular – an arm not of menace or threat or even sex, though it’s those things too, but of authority. It’s the arm of someone who has been changed, who has, through the transmogrifying influence of New York’s downtown club culture become someone new. President Nixon had been ousted, the country was in tatters, sex was back, identity was what you will.

(Morris wasn’t gay, though the image trades in the butch aesthetics of the Meatpacking District’s leather clubs, like the Mine Shaft. Once I might have grumbled at this appropriation, but now it strikes me as a savvy nod to gay life’s promiscuous influence on the city-at-large, the freaky coolness of sex.)

I don’t remember how I responded to the image. Perhaps I said, ‘Wow’ – an elastic utterance, itself a burp of change and a harbinger of it. An inverted ‘Mom’, the mama of wonder and confusion.

‘My theory,’ the house-sitter said, ‘is that if you laid out this sculpture, ‘you’d see something.’

‘What would you see?’

‘An elephant. Like Dumbo.’ The eponymous elephant star of Disney’s 1941 feature-length cartoon.

‘Why Dumbo?’

‘Do you remember the scene when he gets high and everyone around him turns to bubbles? This is the bursting bubble made felt and tacked to the wall. A reminder of passing highs, you could say.’

The writer was either wrong or playing with me, suggesting only the absurd to see how much of it I would gobble up. All of it, as it turns out, since I sat for the rest of the night, as wine and noodles flowed, concentrating on the deflated elephant on the wall. Its form, like much of Morris’s sculpture, possessed an almost risible, surreal promise, as if at any moment it might fill with gas and become a Really Living Thing. But what, or who?

I saw its limbs inflate, its belly rise, its head take shape. But it was no elephant, it was something – someone – else. It fattened as it continued to climb over our drunken forms sprawled on the floor, among the books and sheets of paper. Its wings and limbs and other loose bits flapped and whipped the air. It threatened to bump the art off the walls, to blow us out the window. It was everything and nothing, completely unrecognizable as any creature or object – a thing only to be awed for its capricious formlessness. It was New York, it was the writer, it was the river out the window, it was a place to stumble into, a being-as-landscape. It was no Dumbo, nor one of Dumbo’s mescaline-dreamt friends, though it was them, too. It could have been me, or Robert Morris. No matter, it never quite cohered. Eventually it returned to its spot on the wall, where it belonged – less sculpture than vision.

Main image: Robert Morris inside Box for Standing, 1961. Courtesy: Castelli Gallery, New York; photograph: © Grant Delin