What Does Identity Mean to Maria Eichhorn?

Ahead of the artist’s contribution to the German Pavilion, Adam Szymczyk considers how she might embrace the loaded history of the country she will represent

Ahead of the artist’s contribution to the German Pavilion, Adam Szymczyk considers how she might embrace the loaded history of the country she will represent

Read a German language version of this article here.

How old is ancient, and what is contemporary? And what is it that makes the German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale so different, so appealing? Invited to represent Germany in Venice this year, Berlin-based artist Maria Eichhorn acknowledges – with her characteristic brevity and modesty edging on irony – ‘a sense of the seriousness and responsibility artists before me have attached to this task.’1 Eichhorn elaborates that she always conceives of that responsibility to address history in her work as a contemporary task rather than an immutable debt: ‘My works are primarily concerned with the present. So, how do we deal with the aftermath of our history today? The pavilion is obviously also a part of history and we are influenced by it today – whether we like it or not. But you don’t have to deal with the pavilion, although artists [who worked there] have time and again made site-specific statements in their contributions. It is interesting to see that this pavilion demands such site-specificity. Yet, there have also been contributions that distanced themselves from it, or took a distance from this distancing.’2 That last phrase seems crucial for imagining how Eichhorn’s work can critically reflect history within the current political condition of a globalized world, in which the unchanged political geography of the Giardini – where fewer than 30 countries have dedicated national pavilions, with other participating nations having to rent off-site spaces – seems thoroughly anachronistic. The sediment of the 20th century, in the form of state-owned buildings occupying the gardens, is even more palpable during an off-season visit, when the pavilions feel strangely abandoned, hollowed out, stripped of nationalistic aspirations and pride.

The structure now known as the German Pavilion was built by Milan-born architect Daniele Donghi as a neo-renaissance ‘Padiglione Bavarese’ (Bavarian Pavilion) in 1909. In 1938, on the initiative of Adolf Ziegler, president of the Reich Chamber of the Fine Arts, the pavilion underwent institutional transformation into a branch of Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) in Munich and was correspondingly redesigned by architect Ernst Haiger, who – as well as authoring other buildings in Nazi Germany – designed the bar of today’s Haus der Kunst, Munich. For a contemporary visitor, the German Pavilion still retains the cold, stately elegance of its 1930s revamp, despite the postwar removal of Nazi symbols from the facade and changes to the interior aimed at making its proportions and layout less overwhelmingly authoritarian. Addressing the ideological connotations of the pavilion’s architecture in the context of the biennale, Hans Haacke pointedly took on the building’s material and historical substance in his work Germania (1993) – by methodically demolishing its marble floor. Haacke’s extreme site specificity extended to installing an enlarged black and white photograph of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini visiting the 1934 Venice Biennale against a red background at the entrance to the building, recalling the colours of the Nazi flag. Lateral galleries were filled with Nam June Paik’s epically proportioned video installation Marco Polo (1993), which explored the connections between Asia and Europe through the life of the Venetian merchant. This pairing of works was an early instance of transnational use of the pavilion, which also earned both artists the Golden Lion. Haacke’s take, however, did not allow for the use of transculturality as an excuse for historic amnesia and was sourly received in most of the German press at the time. Germania obliterated the attempt at a depoliticized dialogue of cultures that the German Pavilion had been declared to represent in the prize ceremony speech. In 2022, one can’t visit Venice’s famed gardens without looking beyond the setting of an art exhibition: bloody wars, human-made crises of migration, destruction of the natural environment and new warmongering of superpowers, most recently in and around Ukraine.

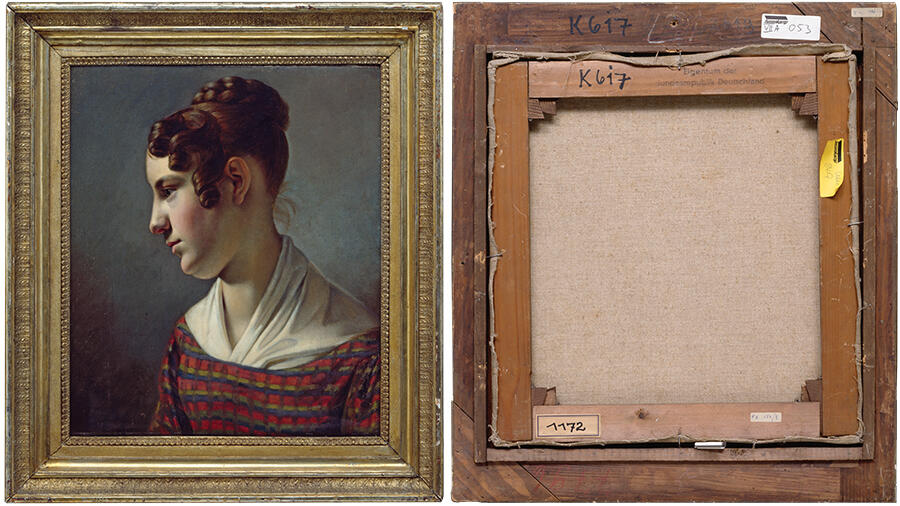

Since the early 1990s, Eichhorn has been enquiring into matters of importance in society while taking distance from the trend towards thoughtlessly scrolling through an ever-changing roster of political topics and so-called alternative facts in our (social) media-driven, supposedly post-political era. For the Kassel iteration of documenta 14, for instance, where I was artistic director in 2017, Eichhorn established the Rose Valland Institute (2017–ongoing), a multi-pronged work dealing with the question of systemic looting of Jewish property under the Nazi regime. This seemingly dormant issue had been made current again by the heated debates that began in November 2013, when Focus magazine made public the discovery by the representatives of the public prosecutor’s office of around 1,600 artworks amassed by Hildebrand Gurlitt, a German art historian, museum director and art dealer working for the Nazi state.

When asked to summarize her project for Venice, Eichhorn raises the question of accessibility as a central concern: ‘The work is accessible. It can be experienced both conceptually and – physically and in motion – on site.’3 Accessibility is a much-mythologized issue for contemporary cultural institutions, including museums and biennials. There’s no doubt that Eichhorn – whose work is often described as institutional critique – is aware of this. We can only imagine the consequences of her embracing radical accessibility in a world that, more than ever, seems organized around the notions of borders, eligibility and exclusion. Eichhorn makes her position even clearer by delegating an important part of the work to the visitors: ‘The accessibility of my work is important for me particularly in these big exhibitions. That’s why I always try to put in place multiple levels of access in order to make it easy for visitors to perceive the work. I always also try to put the audience in the position of deciding whether they want to relate to the work in an active or passive way. Each person can attach their own thoughts to it, can start doing something else with it, can bring in their own background, their own thoughts and experiences every time.’4 Thus described, accessibility is not merely an issue of technocratic regulations of physical access, but of probing the degree of political agency of subjectivities in making meaning in the world. Eichhorn takes a stand on the question of what role art plays in enabling unconditional access, beyond the confines of national representation: ‘Even if it is shown in national pavilions, art remains, as I understand it, international and cosmopolitan, anarchic, resisting, political and polemical, fragmentary, critical and independent. It is only a passing phase, showing it in these pavilions and in these contexts. Art remains independent from them.’5 Rather than making a plea for the absolute autonomy of art, Eichhorn points to a possibility of art that opens a political space beyond the control of the state.

Sometimes the floor must get broken so that the work can resume somewhere else. In 1993 – the year of Haacke’s Germania – I experienced Eichhorn’s work for the first time, while a curatorial assistant at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw. Here, she realized her project Nordwestturm (Die Wiederaufnahme der Arbeit am Nordwestturm) (North-West Tower [Resumption of the Work on the North-West Tower]) by plastering the brick elevations of the tower of the former royal residence. Damaged during the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, the original baroque palace of Ujazdów was demolished and rebuilt between 1974 and 1985 to house a new centre of contemporary art, which started to operate with renewed energy in 1989, during a period of political and economic transition in Poland. While the centre hosted a newly created contemporary art collection and temporary exhibitions of Polish and international artists, its four elevations remained unfinished due to a shortage of funds that occurred during the protracted reconstruction process. Eichhorn’s proposal saw the production budget for her show diverted into plastering one tower of the castle as a contribution to the completion of the restoration. Accessible to all, the beige-plastered tower was a visible anomaly in the park surrounding the castle, jutting up strikingly from the red-brick structure whose elevations and remaining three towers stayed unrendered. The artist’s intervention – a resumption of the reconstruction work, which was temporarily interrupted and limited to a fraction of the building – had far-reaching implications, positioning the tower at an intersection of past, present and future. Rather than performing a blatant critique, Eichhorn tapped into the history of the building and slyly exposed the institution’s volatile financial reality against the backdrop of Poland’s rapid and brutal economic transformation at that time.

Nearly 30 years later, asked about her response to the architecture of the German Pavilion as a symbol of the Nazi era, Eichhorn responds: ‘I share the view of Hans Haacke and others that, historically speaking, the pavilion should be preserved as a monument. History, which also conveys itself to us in architecture, can’t just simply be dismantled and belied, as with the Palast der Republik in Berlin, which was replaced with a fake Schloss.’6 Her terse statement connects the recurring debates around the Nazi architecture of the German Pavilion to more recent ones, brought about by the historicist reconstruction of the Prussian Berlin Palace as a museum of ‘world culture’ – a subject of ongoing controversy and an example of Germany’s memory politics operating at different speeds with regard to earlier colonial history and the country’s recent Nazi past. That this is not just a matter of over-politicizing is evidenced by the relative lack of interest shown by the German media in the exercise of decolonial practice being established by documenta fifteen, while its curators, the Indonesian artist collective ruangrupa, have been framed as anti-Semites following allegations of partisanship of some of documenta fifteen’s artists with BDS, which was declared an anti-Semitic organization by the German parliament in 2019.

We can imagine that Eichhorn’s work for the German Pavilion might become a situated voice in some of the ongoing debates, in which she’s been an active participant for decades, that seek to deconstruct prevailing attitudes. As she notes: ‘The German Pavilion is symbolically charged and presents a challenge to artists on several very different levels. With every attempt at deconstruction, you’re confronted with that fact, but it also makes it fun. Without departing from that aspect, I regard the German Pavilion not as isolated, but as part of an ensemble and engaged in interplay with other pavilions and other country participations in terms of national-territorial and geopolitical, global-economic and ecological developments.’7

And that’s what makes the German Pavilion so different, so appealing, as a place in which to both make work and look beyond. Commenting on her position as an individual artist grappling with that overdetermined context, Eichhorn hints at a different understanding of identity, beyond one particular affiliation – the one that evades the cul-de-sac of identity politics by receding into the background when the work is done: ‘Most of the artists who do a Biennale pavilion, including the German Pavilion, simply see it as an assignment either to pursue and exhibit their usual work, or to expose grievances, question politics, initiate forms of solidary exchange between groups of society, take a stance, etc. In my view, an artist is not a representative of a country, but of a certain attitude, a certain way of thinking and acting in relation to a given situation. As for the question of affiliation: I conceive of myself as a mixture of multiple identities and non-identities and distinguish myself from myself. It’s not me as a person but my work that’s supposed to be the focus of the attention. I make my work and then recede into the background.’

Maria Eichhorn's solo exhibition is on view at the German Pavilion of the 59th Venice Biennale from 23 April to 27 November 2022.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 226 with the headline ‘Maria Eichhorn’. For additional coverage of the 59th Venice Biennale, see here.

Main image: Maria Eichhorn, Maria Eichhorn Aktiengesellschaft (Maria Eichhorn Public Limited Company), 2002, exhibition view, Documenta11, Kassel. Courtesy: © Maria Eichhorn/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn and DACS, London; photograph: Werner Maschmann

1 Maria Eichhorn in conversation with curator Yilmaz Dziewior, deutscher-pavillon.org, 17 February 2021

2 Maria Eichhorn interviewed by Gerd Roth for DPA German Press Agency, 29 December 2021

3 Maria Eichhorn in conversation with curator Yilmaz Dziewior, deutscher-pavillon.org, 17 February 2021

4 Maria Eichhorn interviewed by Gerd Roth for DPA German Press Agency, 29 December 2021

5 Ibid

6 Maria Eichhorn in conversation with curator Yilmaz Dziewior, deutscher-pavillon.org, 17 February 2021

7 Ibid