3rd New Museum Triennial

New Museum, New York, USA

New Museum, New York, USA

Since its launch in 2009 with the exhibition ‘Younger Than Jesus’, the New Museum Triennial, now in its third edition, has been devoted to emerging practices and has fast yoked itself to the idea of describing the ideas of a new generation. Naming and claiming young artists walks a line between tiresome fashionability (‘hot artists to watch’) and usefully providing a space in which to engage with an era’s urgent questions. But it also follows that curators are effectively barred from employing the critical ballasting that was rife in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, for example: resuscitating the careers of under-sung artists or setting up art-historical lineages by including respected elders. At the New Museum, this generation must speak for itself. New Museum curator Lauren Cornell and artist Ryan Trecartin have chosen a strong through-line for their triennial – which includes the work of 51 artists from more than 25 countries – looking at the effects of technology on our lives. As long as a decade ago, Trecartin’s compellingly cacophonous videos were exploring the internet as a potential space for narcissism, mutable identity, fantasy and speed – turning them all up to a frenzied pitch – whilst Cornell was previously director of Rhizome, the New Museum-affiliated art organization devoted to new media and technology. The title of their show, ‘Surround Audience’, has all the hallmarks of Trecartin’s carefree, tech-inflected syntax and deftly summons the exhibition’s central line of enquiry: the implications for a highly connected society of subjects aware that they are being systematically observed and analyzed, in ways that they desire and ways that they do not.

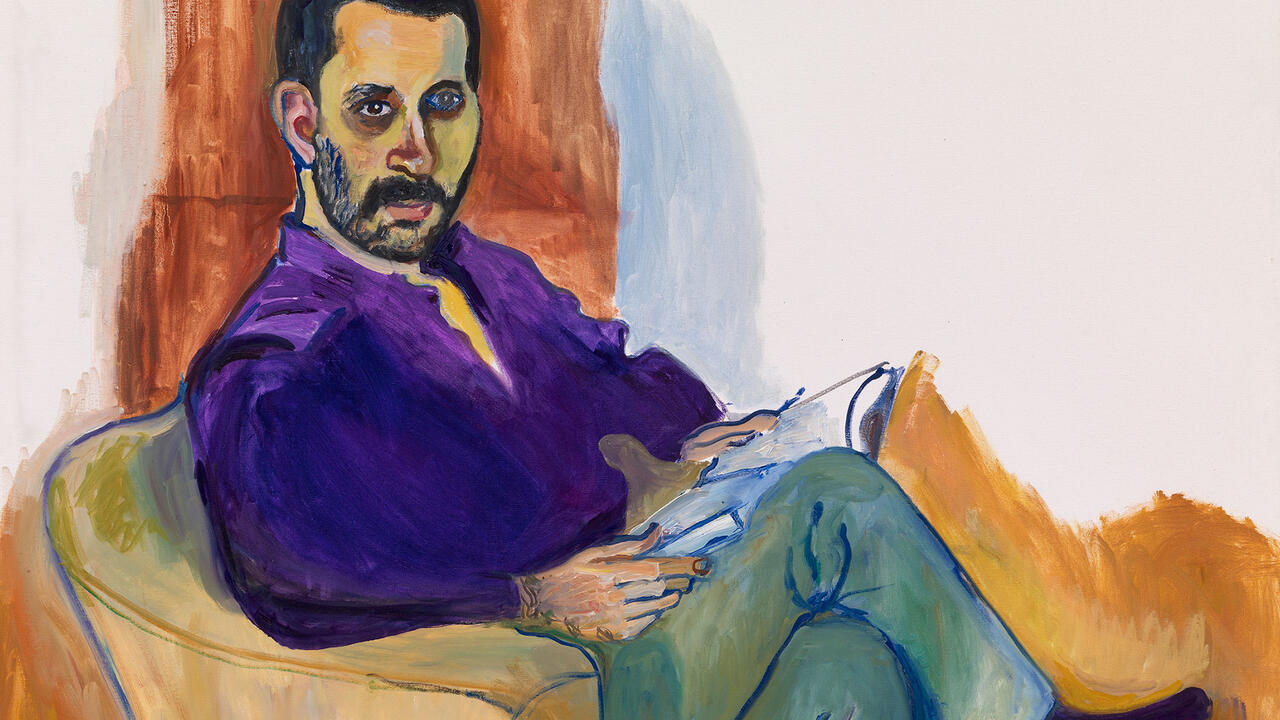

The triennial’s defining moments cleave to this line. The curators make a centrepiece of a dimly lit space on the third floor, pitting various forms of avatar or surrogate against one another. Frank Benson’s iconic nude sculpture Juliana (2015), a regal likeness of transgender artist Juliana Huxtable rendered as an Accura® Xtreme Plastic prototype – her skin painted iridescent green and her hair braided, snakelike and cold – is placed in a face-off against a large projection of Ed Atkins’s video Happy Birthday!! (2014). Atkins’s sympathetic, hyperrealistic avatar, complete with a twitchy eye, holds the body of another sickly figure in its arms. The terminal diagnostic phrase ‘six months to a year’ is repeated over and over, as though the avatar were trying and failing to fathom the words’ implications. He retches – a horrifyingly endless, visceral retch – vomiting a thick black liquid that eventually submerges him. Nearby is Huxtable’s photographic series ‘UNIVERSAL CROP TOPS FOR ALL THE SELF CANONIZED SAINTS OF BECOMING’ (2015), self-portraits of the artist, her skin and hair painted fluorescent colours, alien, accompanied by two all-caps text pictures, shouty hymns to music as a space of escape from ‘A SURFACE MADE OF CLICKS SHARING REPRESENTATIVE DATA FILES, EACH ONE DESTROYING OUR FLESH AS IT FADES INTO NOUMENON’. Significant, then, that Benson’s hyperreal Huxtable is more powerful than her prints. The stronger virtual avatars and hybrid machine bodies become, the weaker the human body seems in comparison.

Josh Kline’s Freedom (2015) is a dystopic rendering of Zuccoti Park’s corporate architecture, in which trees are replaced with mobile phone towers strung with credit cards in place of leaves. The installation is the scene for Hope and Change (2015), a video that uses facial replacement technology to overlay Barack Obama’s face onto that of an actor who gives the President’s inaugural address from an alternate 2009. Those responsible for the financial crisis would be made to pay rather than ordinary citizens. Preventing environmental catastrophe would be a priority. It’s the speech that never came – an eerie, synthetic ‘Star-Spangled Banner’, heard as though from a distance, reminds us that this is a collective fantasy, hope’s ghost rendered in pixels. As the scene of the Occupy Wall Street movement, Zuccoti Park is haunted by other ghosts. Four riot police Tellytubbies stand guard; on the television screens in their stomachs, video feeds show retired police officers reading aloud from the social media feeds of various activists.

Though it is possible to identify a number of shared concerns across the exhibition, the overall choreography could be stronger. For example, works with shared material or aesthetic concerns – mutability, liquid, the void, anthropology, material history – are distributed throughout. The horror vacui seen in Atkins’s video is mirrored in Peter Wachtler’s stop-motion animation HCL H264 (2012), of a pair of wired-together crutches limping through a dark desolate space while insisting ‘I’m the BEST. Yes. ME!’ There are echoes, too, in Casey Jane Ellison’s digital zombie-marionette video of herself giving a flat standup routine to an audience of none (IT’S IMPORTANT TO SEEM REAL II, 2015) but these relationships are not suggested by the pieces’ scattered installation.

Yet this is possibly part of our broader contemporary predicament. Much of this work is purposefully egomaniacal and points towards the hysteric self above other shared concerns. And if this is indicative of this generation, then the political future looks dim. There’s a discernable terror evident in this show that, for all our broadcasting, we might not really be talking – a fear that we are becoming a bunch of lonely, narcissistic egos performing for cyberspace and therefore not partaking in broader politics. (Though it’s worth noting that the politics of self-representation clearly remain important for those who are not recognized, heard or seen enough.) With so many artists pointing to the individual self, it’s perhaps significant that the most prominent collectives in the show are groups who have chosen to intervene directly in corporately defined culture and advertising. New York-based DIS contribute a slick kitchen ‘island’ for discussion (The Island [Ken], 2015), and K-Hole, now familiar beyond the art world as the group that defined ‘normcore’, provide the triennial’s marketing campaign using a friendly blue and yellow pharmaceutical pill and phrases such as ‘WE REALLY TRIED THIS TIME’ (Extended Release, 2015). Such approaches amount to a discomfiting take on capitalist realism – tough to fully subscribe to, but certainly understandable. What’s the point of institutional critique in the museum when power is in the hands of corporations?

There are clearly thrills here as well as anxiety. In an untitled animation by Oliver Laric (2014–15), cartoon characters undergo a transformation – from beast to man, young to old, alien to girl – to demonstrate the fluidity of identity, whilst Aleksandra Domanovic´’s hybridized prosthetic hand sculptures covered in ‘Soft Touch’ paint with a realistic ‘skin feel’, appear to have evolved or been customized to include teeth or tools (SOHO [Substances of Human Origin], 2015). Human skin, however, seems tragically fragile and imperfect within the space of ‘Surround Audience’, appearing only at the peripheries of the exhibition and even becoming a source of comedy. Ellison points at her face in one episode of her deadpan talk-show, Touching the Art (2015), shown in the museum’s lobby, and offers that it’s easy to tell that she’s not doing so well financially, because if she was then ‘all of this would be lazered’. Steve Roggenbuck yells into his handheld camera in a rainy field, his nose red raw and his skin blemished with acne, in make something beautiful before you are dead (2012) in the basement: ‘Everything dies because everybody dies … Guess who you can’t hug when you’re dead? Everyone.’ The jerky, funny video makes continual calls to intimacy and empathy, though Roggenbuck is still wailing into a kind of void. Occasionally, I wonder about the peripheral placement of non-Western artists. South African artist Donna Kukama’s NOT YET (AND NOBODY KNOWS WHY NOT) (2008), an intervention in which the artist calmly covers her face with lipstick in a Nairobi Park during a commemoration of the violent Mau Mau rebellion against British rule in Kenya, is shown in the stairwell.

‘Surround Audience’ foreshadows a world that is increasingly hostile to human frailty. Messy materiality looks as though it is destined for the museum. And yet, certain artworks that focus on the transformation of materials are some of the most powerful. Lawrence Abu Hamdan deals texturally with noise pollution in Cairo by investigating the qualities of cassette-taped sermons subject to multiple re-recordings. (Tape Echo, 2013–14). Olga Balema’s horizontal, clear-plastic sacks of water on the floor, in which are suspended oozy, deteriorating shards of metal and paint (Untitled, 2015), are sealed off for safety, perhaps the liquid heirs to Carl Andre’s floor sculptures. Tania Pérez Córdova places borrowed items temporarily in sculptural stasis – a moment of still and quiet is granted to a SIM card gently caught in terracotta (Meeting a stranger, afternoon, cafes, 2014). Looking at an earring borrowed from the artist’s grandmother, strung from a fragile bronze cast of a quiet corner of the New Museum (We focus on a woman facing sideways Evening, 2014), the host institution’s name suddenly rings strange, suggesting a future anthropological museum devoted to the fragile remains of this outgoing human culture. But we haven’t entered the void just yet. We still have skin in this game.