Arturo Kameya’s Quest Towards the Supernatural

At Grimm, New York, the Peruvian artist presents a body of work that asks us to defang our baleful understandings of ghosts

At Grimm, New York, the Peruvian artist presents a body of work that asks us to defang our baleful understandings of ghosts

In 1993, a Peruvian television show declared that Sarah Ellen Roberts would be resurrected from her grave on the 80th anniversary of her death: 9 June 1913. Born in Lancashire in 1872, Roberts was allegedly sentenced to death for vampirism and her husband forced to travel the world in search of a graveyard that would bury her. Although few facts about Roberts’s life are known, records show that she went to Peru with her husband in 1913 to visit her brother-in-law, who worked at a cotton mill in Lima. The media sensation that developed around her potential resurrection, however, morphed her into a miracle-worker and she became known as La Santa Vampira (The Holy Vampire), inspiring hundreds to flock to her grave with offerings and requests.

Writing about this incident in a newly published catalogue of his work, Who Can Afford to Feed More Ghosts (2021), artist Arturo Kameya describes Roberts’s corpse as having ‘travelled through time from modernity to postmodernity’ – a temporal overhang between different traditions, culture and media that pervades his practice. This idea is crystalized in Tutorial (all works 2021), a small but potent painting in an exhibition of his new work at GRIMM in New York. The painting depicts the modern afterlife of tradition: an open laptop featuring a YouTube tutorial for a spiritual cleansing ritual. On the table are a knife, two halves of a clove-studded lemon, a candle and a candle holder. Kameya remembers being aware of these observances and superstitions as a child growing up in Peru but, unable to recall them exactly, he has looked them up on YouTube. There are many phantoms in Kameya’s work, particularly this intergenerational information seepage, and the mediated spaces that archive and warp it. His work suggests we adopt a more capacious definition of the term ‘ghost’, defanging its more malignant Western undertones for an animism that mixes memory, media and ancestry.

Kameya’s ghosts are invoked through oneiric installations and paintings drawn from grainy photographs. Afterparty, which depicts a makeshift ancestral shrine, refers to more conventional notions of apparitions: acts of care and worship that cross the boundaries of life and death. The surface is muted, with the patina of an aged penny; it appears weathered, as if having been exposed to the sun and rain for many years before arriving in the gallery. (An effect the artist achieves by mixing clay powder into his paint.)

Cage is inspired by his childhood bedroom – an area sectioned off from the main space using cabinets and armoires. Some photographs are taped to the wall above one of the mattresses on the floor. A caged animal sits atop the dresser. This architecture extends into the gallery in The Wait, a whimsical installation featuring two men crouched opposite each other looking at their phones; in front of them, a fish has been turned into a swimming pool, complete with lane markings, for a group of lounging cockroaches. These dioramas, which feel like an extension of his installation Who can afford to feed more ghosts (2021) at the New Museum Triennial, heighten our perceptivity of the supernatural.

Occasionally, the artist’s subjects become explicitly fantastical. Fleas dream of buying themselves a dog, but dogs just want to go to outer space, the largest painting in the show, depicts a gang of street dogs enacting a New Year’s ritual of Kameya’s youth: burning old furniture. The space depicted is again based on his parents’ house, the walls propped up by wooden planks like a theatre set. Faded pictures hang off the walls; cloth rags droop from the tops of burning poles. In the distance, a comet streaks across the sky. We might imagine this scene as a depiction of another urban legend, like that of La Santa Vampira: yet more evidence of the spiritualism that operates all around us.

‘En esa pulga se mezcla nuestra sangre’ (In that flea, our blood mixes) is on view at GRIMM, New York, until 15 January.

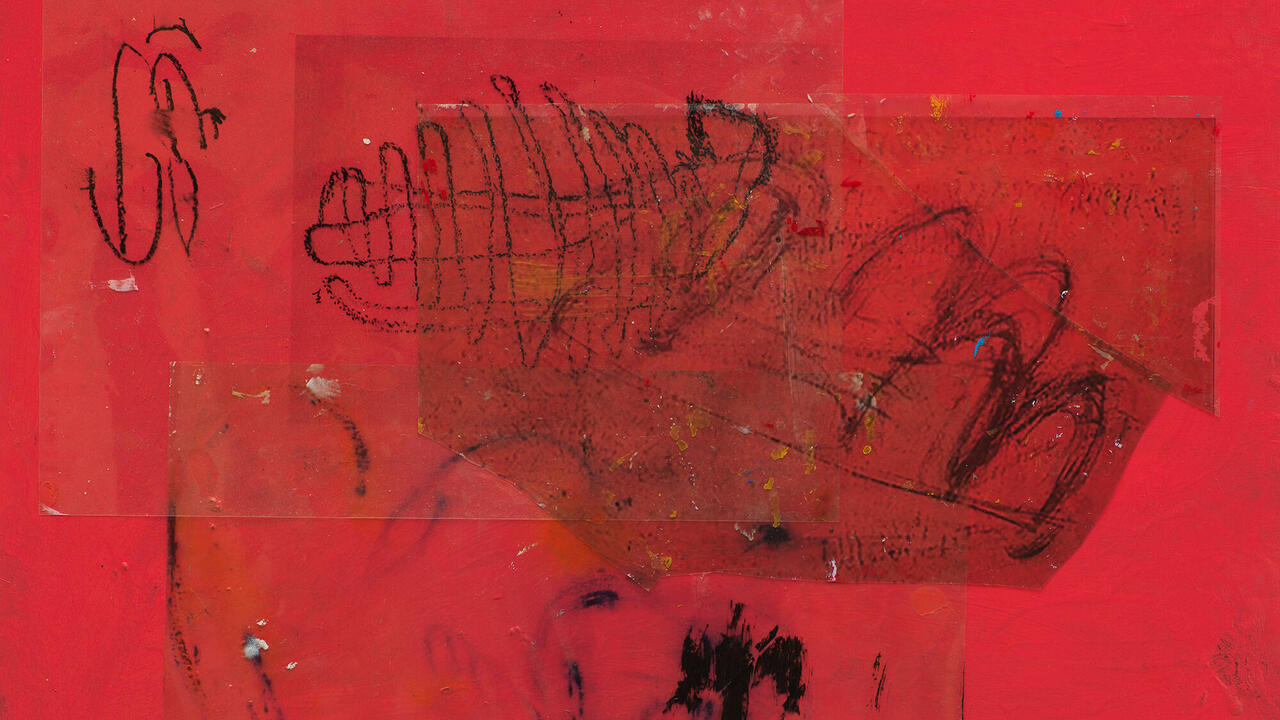

Main image: Arturo Kameya, 'In that flea, our blood mixes', 2021, exhibition view, GRIMM, New York. Courtesy: the artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam/New York