A Cathode Ray Séance

A day long programme of film screenings, talks and readings is dedicated to British science fiction and horror writer Nigel Kneale at New York's Michelson Theater

A day long programme of film screenings, talks and readings is dedicated to British science fiction and horror writer Nigel Kneale at New York's Michelson Theater

Walking home from dinner in New York’s East Village the other night I heard the approaching throaty drone of a low-flying plane. I didn't pay it much attention but it was loud enough for me to clock it. On a quiet street just north of my apartment on the Lower East Side, three guys emerged from a building on the east side of the road. They stopped to look up at the sky and I followed their gaze. The plane was passing almost right above us, heading north, parallel to the east river Manhattan shoreline. I suddenly became aware of a flat, triangular, green laser beam sweeping the street from the plane. The beam passed over the trio ahead, then me. This green ray looked like a giant bar-code scanner reading every contour of the street. For a brief second it was like being caught in a bad light show at a 1990s rave. I caught up with the three guys. We all looked at each other, then back up at the sky. The plane and its laser disappeared over some nearby tall buildings in the neighbourhood. ‘What the fuck was that!’ ‘I thought that was you takin’ a photograph!’ ‘Did you see that?’ ‘What the…?’ I continued home. Unlocking the door to my apartment block I heard the plane coming back, flying south. I watched it's green eye strafe ground just a little further west of where I'd been walking.

The previous day I had been at ‘A Cathode Ray Séance: The Haunted Worlds of Nigel Kneale’, a day long programme of film screenings, talks, readings and performance at NYU’s Michelson Theater, dedicated to the British science fiction and horror writer Nigel Kneale. Still mulling over the ideas raised at the event – rationalism and superstition, science and paranoia, deep pasts collapsing into near futures – I couldn’t have picked a better weekend to be zapped by a mysterious green ray on a near-deserted street at night. Coming just weeks after Hurricane Sandy too, I was getting used to seeing the odd and unsettling in the neighbourhood. Was it the power of suggestion that conjured this mysterious aircraft into existence? Was I losing my mind? I began to feel like David Vincent, the architect who witnesses a UFO landing at the start of the cult 1960s series The Invaders: ‘It began one lost night on a lonely country road looking for a short cut that he never found. It began with a closed, deserted diner and a man too long without sleep to continue his journey. It began with the landing of a craft from another galaxy…’ I was later to find out the explanation was more terrestrial than beachhead from outer space, but no less full of Knealean foreboding. My mind – as far as I could tell – was intact.

Kneale, who died in 2004, is scarcely a household name. He’s best known as the author of the Quatermass television plays and films (which, when originally screened in the UK in 1953 were watched by a third of all UK TV owners). Yet with his chilling 1954 adaptation for the BBC of George Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty Four (1948) and screenplays such as The Road (1963), The Year of the Sex Olympics (1968), The Stone Tape (1972) and Murrain (1975), Kneale evolved a uniquely haunted form of science-fiction, one that fused the white heat of technology and broadcasting with rural occultism, and drove parapsychology headlong into Cold War fear. With their ominous BBC Radiophonic Workshop soundtracks and infusions of eldritch dread into the dreary landscapes of post-war Britain, Kneale’s screenplays – inheriting the restrained malevolence of ghost story writer M.R. James – have exerted a strong influence over a number of musicians and writers, not to mention those like myself who were terminally spooked by re-runs of his work, stumbled across as a kid on rainy Saturday afternoons spent in front of the TV. Pink Floyd, Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, John Carpenter, Patrick Keiller, Chris Carter (who originally approached Kneale to write The X-Files) Broadcast, the Ghost Box record label, The League of Gentlemen, China Mieville and Mark Fisher have all cited Kneale as an influence on their work, and in recent years his work has also become a touchstone for hauntology – a strain of critical theory embracing architecture, literature, film, pop music and politics that perhaps hit the height of its popularity a few years ago, but for which there is a lingering fascination.

‘A Cathode Ray Séance’ was organized by Mark Pilkington of Strange Attractor Press – celebrants of the weird, wonderful and all that remains resistant to the steamroll blandification of culture – and writer and critic Sukhdev Sandhu. Sandhu’s Colloquium for Unpopular Culture – the umbrella for this event – is one of the best-kept secrets of the New York talks circuit. Started in 2007 with James Brooke-Smith, the Colloquium – a word-of-mouth gathering that has no website or Facebook group with which to advertise itself – has explored channels between global cinema, music and politics, tuning into signals from cultural studies, theory and pop often drowned out by mainstream transmissions. It has included series with titles such as ‘The Speed of Your Hair’ and ‘Auscultations: Sound, Noise, (Nervous Heart)beats’ and addressed topics ranging from punk in Africa and Arthur Russell, through CLR James, Stuart Hall and John Berger to North Korean sci-fi, Pakistani pulp cinema, P.O.W. gardening, the Southall Black Sisters, and Wang Bing’s West of the Tracks (2003). Speakers have included Teju Cole, Bilge Ebiri, Mark Fisher, Coco Fusco, Steve Goodman, Chris Petit, Aman Sethi and Lawrence Weschler. (Full disclosure: last year I gave a short talk for the Colloquium about northern soul, at a screening of Tony Palmer’s poignant 1977 documentary Wigan Casino.) As Sandhu put it in his opening remarks for ‘A Cathode Ray Séance’, often these events could be characterized as people in a room looking at each other and thinking ‘what, someone else is into this stuff too?’

This certainly described the genial assortment of writers, artists, film curators, musicians, and sci-fi heads – not to mention a young man dressed in a flowing purple cape – crammed into the stuffy theatre at NYU for ‘A Cathode Ray Séance’. Our first step into the Knealean outer limits began with a screening of The Stone Tape, introduced by Dave Tompkins, music writer and author of How to Wreck a Nice Beach (2011). Balancing the event’s dangerously heavy lean towards British esotericism, Tompkins described the impression made on him by The Stone Tape after watching it as a child growing up in North Carolina. Given his interests in the history of recording technology, his connection to the film made sense. The Stone Tape is the story of a group of scientists working for an electronics corporation, developing new home audio equipment. Their research laboratory is relocated to a large manor house, constructed in the Victorian era around the remains of a far more ancient site. A storage room in the house becomes the epicentre of a number of terrifying spectral encounters with the ghost of a young Victorian maid, her disembodied screams repeated mechanically as if on a tape recording. Initially skeptical, the scientists begin observing the phantom phenomena. They find that the room itself is a form of recording device; centuries of trauma embedded into the stone walls and replayed on loop, triggered by the sensitivity – or receptivity – of a visitor to the room. Despite some distractingly large shirt collars and flared trousers, and a lead male character of almost comic sleaziness, The Stone Tape is genuinely unsettling, thanks in no small part to the abrasive and fractured BBC Radiophonic Workshop soundtrack and audio effects. The Stone Tape puts the core engine of suspense in sound rather than what’s on screen. The horror resides in what the scientist’s computers and recording devices cannot register. Yet the texture of 1970s videotape that its filmed on – smudgy ‘ghostings’ and acid-like trails at the edge of anemic coloured images – serves also to emphasize a slippage between the scientific and the supernatural; between the probes, dials and sensors of the machine-recorded world and the psychic videotape of the imagination.

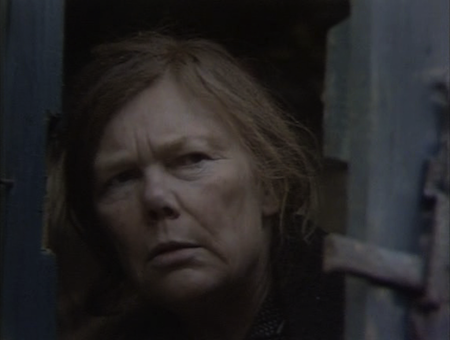

Next up was Murrain, a one-hour teleplay, introduced by journalist and filmmaker Bilge Ebiri. Murrain – set in Derbyshire, and shot on deathly pale colour film – concerns a young veterinarian called to a remote village to investigate an unexplained livestock disease on a local pig farm. The farmer and a group of his friends try to convince the vet that the disease has been caused by an elderly woman who lives alone near their property, and who they believe to be a witch. The vet is scornful of their superstition, suspecting instead that the woman is being victimized and is in need of help from welfare services. He visits her home and finds she is living in squalid conditions, unable to look after herself properly as the locals won’t sell her groceries or household supplies out of fear. As he attempts to help her – buying food, calling social services – his belief in science is slowly eroded by the ideas of witchcraft that the locals have planted in his mind; that objects she has touched carry a hex (they blame a jar of berries she gave to one of them as the reason he has developed walking difficulties), that she used her cat as a remote viewing device (until the villagers cut it in two and threw it over her garden wall). Murrain ends ambiguously, with no resolution, no conclusion about the cause of the illnesses or whether the woman possesses any supernatural power. With its tightly composed close-ups of faces, slow pace and spare use of background sound rather than the emotional cues of a music score, Murrian is powerful drama, its atmosphere grim and threatening. There are no special effects, no scenes of paranormal activity. Rather, it is a play that argues science and superstition are nothing more than two equal belief systems, and that the modernity represented by the vet’s medical kit and car, and the industrial quarry he passes on the way to the farm – a new technological scratch into the deeper history of the land – co-exists with trust in older knowledge structures. As in The Stone Tape, the world Kneale creates here is one of material equivalence and relativity; objects have an equal potential to be invested with power; be it a jar of berries, a stone wall, or state-of-the-art computer equipment. It is a world about competing symbolisms, conflicting factions pitting one form of tools to represent the world against another.

A panel discussion followed, chaired by Sandhu, with contributions from Pilkington, Dave Pike, Professor of Literature at American University, Washington D.C., and Will Fowler, Curator for Artists’ Moving Image at the British Film Institute, London (and, with Vic Pratt, responsible for the BFI’s excellent Flipside strand). The conversation compared American with British television culture – how a narrow range of channels in the UK, and ownership of television spiking around the time of Elizabeth II’s coronation (one year before Kneale’s 1984 and Quatermass), led to his work having a large, and largely captive, audience. Comparisons between Kneale’s work and that of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone series – created roughly contemporaneous with Quatermass, and similarly concerned with science and the paranormal – suggested that resolved, self-contained narratives characterized US approaches to screenwriting, as opposed to open-ended stories such as Kneale’s Murrain or The Stone Tape. The panelists discussed how differing relationships to landscape and history suggested one reason why Kneale’s screenplays had a particular force in Britain that couldn’t be mapped onto the American experience. The relatively compact size yet deep history of the UK has led to a vertical, stacked sense of the past: Modernist housing developments erected next to Victorian terraces. Medieval castles founded on Roman ruins. Nuclear submarines submerged in ancient lochs. (I grew up in an area brimming with Knealean ingredients and a sense of history being something liquid and ever-present. Within easy striking distance of my home town are Neolithic standing stones, an Anglo-Saxon burial ground, Civil War battlefields, a major car factory, and an RAF airbase used during the Cold War by the US military. New Age travelers – prototypes of whom crop up in later Quatermass films – used to throw parties nearby on the occasion of solstices and other pagan festivals.) By contrast, the vast scale of the US results in a more horizontally spread sense of the past – there is space to move, to stretch out; the experience of history here is not always one of extreme period juxtaposition. Arguably, Kneale’s writing is less about hauntings in the paranormal sense, than being haunted by history; by aggregations of belief and technology built over centuries that give ragged, uneven contours to our present landscapes.

‘Baby’ – an unintentionally camp and funny episode from Kneale’s TV series Beasts (1976), in which a couple expecting a child discover the remains of an unidentifiable animal buried in the walls of their country cottage – was prefaced by writer and Bidoun senior editor Michael C. Vazquez reading Joanna Ruocco’s short story ‘Manx Sword Dance To A Tarantella In Zero Gravity’ (2012). Written specifically for The Twilight Language of Nigel Kneale – a book produced by Sandhu, beautifully designed by Rob Carmichael and including contributions from Sophia Al-Maria, Bilge Ebiri, Mark Fisher, Will Fowler, Ken Hollings, Paolo Javier, Roger Luckhurst, China Mieville, Drew Mulholland, David Pike, Mark Pilkington, Dave Tompkins, Michael Vazquez, and Evan Calder Williams – Ruocco’s almost sculptural sense of language seemed to channel the ghosts of William S. Burroughs and Donald Barthelme into a deliriously surreal narrative about a group of hippies and a mysterious dome erupting from the earth. Kneale grew up on the Isle of Man in the 1920s and ‘30s, hence the Manx reference in Ruocco’s title. This echoed one of the highlights of the panel discussion, in which Pilkington recounted the story of Gef the talking mongoose; a still unexplained haunting from the Isle of Man in the 1930s, and which during Kneale’s childhood was a tabloid news sensation.

After screening the Hammer studio version of Quatermass and the Pit (1967), ‘A Cathode Ray Séance’ ended with The Road, a performance by Pilkington, Rose Kallal and Micki Pellerano. Spectral looping film projections gave visual shape to a battery of dramatic, brooding analogue synthesizers and tapes (looking much like the ghost monitoring equipment used by the scientists in The Stone Tape), and a reading of Kneale’s now ‘lost’ TV play The Road (wiped by the BBC to make room for new videotape), about a haunting of the present by the ghosts of a future nuclear apocalypse.

If you’ve read this far you’ve probably got a sense of why my UFO encounter the following night felt so apt. The day after the green ray buzzed me, I emailed a few scientifically-minded friends – people I also trusted to not call the men in white coats to come and get me – to ask if they could help explain what I’d seen. My initial theory was that the aircraft was gathering data for Google Maps, to which one friend replied ‘it’s a pretty rum state of affairs when the first thing that comes to mind after being bathed in a mysterious green light by an unidentified flying object is “Google Mapping Project”.’ The most likely explanation is that the plane was making a LIDAR scan of the Manhattan shoreline. LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) is a form of airborne 3D mapping with a range of applications, from law enforcement to archaeology. As reported by the New York Times, recent LIDAR flights over the city have been used to map wetland and flood-prone areas of New York, information that has now gained a new urgency in the wake of Sandy. So it wasn’t an alien space probe. But it was technology in the service of prophesying possible future trauma, data gathering to map the contours of destruction yet to happen. What could be more Nigel Kneale than that?