Return of the Serial Killer: How Psychosexual Male Panic is Infecting Pop Culture

In the age of #MeToo, does the recent proliferation of films and TV shows about serial murderers hint at a troubling resurgence of sociopathic masculinity?

In the age of #MeToo, does the recent proliferation of films and TV shows about serial murderers hint at a troubling resurgence of sociopathic masculinity?

On 12 December 2017, Lauren Berlant posted an article on her blog, Supervalent Thought, titled ‘The Predator and the Jokester’. In the opening paragraph, she wrote:

Al Franken has said he’ll resign. If so, he will be gone from the Senate not because he was a vicious predator but because there was a bad chemical reaction between his sexual immaturity, his just ‘having fun’ with women’s bodies, and this moment of improvisatory boundary-drawing that likens the jokester to the predator. What’s going on?

Berlant argues that US Senator Franken thought his ‘good guy credentials separated him from the predators’. The delineation between good guy and predator is also the focus of David Fincher’s Netflix series Mindhunter (2017) and Netflix’s Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes (2019). Both shows explore the phenomenon of the 1970s serial killer. What the decade birthed, however, was not simply a new criminal taxonomy, but a new kind of masculinity that had to engineer a new mode of catharsis for itself in order to respond to the increasing socio-economic liberation of women. Bundy’s earliest documented homicides were committed in 1974 and targeted sorority girls on college campuses around Washington State. During the first half of 1974, female college students disappeared at the rate of about one per month.

The Ted Bundy Tapes – along with the almost-nostalgic, Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile (2019) and Lars Von Trier’s serial-killer feature, The House That Jack Built (2018) – is illuminating not because it uncovers the reason Bundy murdered women, but because it reveals that Bundy could only perform male normality if he was killing women. Just as acting normal is what it took to get away with murder, normality, a restorative valve, becomes the affective mode that deploys male transgression. Much to the frustration of Stephen Michaud, the journalist who recorded roughly 100 hours of interviews with Bundy in 1980 at the Florida State Prison, where he awaited execution, Bundy refused to blow his cover. (He finally confessed in 1989, only a few days before his electrocution.) It is the ‘good guy credentials’, as Berlant puts it, that enabled the transgression. Male violence, therefore, is not an aberration or a surplus; normalcy is. ‘I don’t feel guilty for any of it,’ Bundy said about his crimes. ‘I feel less guilty now than I’ve felt at any time in my whole life. About anything. I mean really. I am in the enviable position of not having to feel any guilt. Guilt is this mechanism we use to control people. It’s an illusion. It’s this kind of social-control mechanism and it’s very unhealthy.’ Bundy regrets not the murders, but the years he wasted trying to suppress and manage the urge to commit them. He views it as lost time; wasted potential. Self-control becomes synonymous with blockage and emasculation.

Bundy’s two prison escapes (the first lasted six days; the second 46) marked a turning point in both his killing and his thinking. Once Bundy was apprehended and convicted, he was freed from upholding the good-guy act that interfered with unencumbered violence: it was getting caught that provoked him to go on increasingly reckless killing sprees as a fugitive. Judging from the bootleg audio of disgraced comedian Louis C.K.’s set in December 2018 – performed at the Governor’s Comedy Club in Long Island, less than a year after he was accused of sexual harassment by numerous women – C.K. forgoes the ‘self-awareness’ of his late comedy in order to go on irrepressible rants about women, the survivors of the Parkland high school shooting and transgender teens. ‘I’m committing career suicide here,’ C.K. tells the crowd. ‘Let’s just go all the way […] My life is over. I don’t give a shit.’ For C.K., who, like Franken, is both predator and jokester, the idea of ‘going all the way’, in spite of getting caught, is, in a sense, a verbal equivalent of the murders Bundy committed during his two escapes from prison.

When Michaud questioned Bundy about his dating history, Bundy told him: ‘It wasn’t that I disliked women or was afraid of them. It was just that I didn’t seem to have an inkling as to what to do about them.’ The preposition ‘about’ is all-revealing here. It reduces one’s relation to women to just two options: extermination or acceptance. The construction of straight, white, post-war masculinity, Bundy tells us inadvertently, literally becomes: what do men do about women? Something had to be done about the newly liberated, feminist women of the 1970s, the question was: what? The decision Bundy made is the real story of The Ted Bundy Tapes. What the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements have brought into sharp focus is the extent to which men have succeeded in seamlessly interchanging compliance and abuse, normality and abnormality, good guy and predator, in various ways – not, as we previously told ourselves, being either one or the other. Bundy, despite his famously brutal and numerous crimes, managed to get married and father a child while on death row.

On 20 July 1979, Ted Bundy spoke in court against his own counsel: ‘Maybe we’re dealing with the problem of professional psychology,’ he told the judge during his trial for the murders of Margaret Bowman and Lisa Levy at Florida State University’s Chi Omega sorority house. When found guilty of both convictions, Bundy told Michaud: ‘They [the jury] refuse to perceive me as being anything that approaches being normal […] I’m just a normal individual.’ This logic is echoed in the Lifetime series You (2018), another serial-killer drama recently picked up by Netflix. You repurposes the romantic comedy genre as a tool for examining male seduction and manipulation, exploring the way social media amplifies the male gaze and is inherently a system of stalking and control. Joe, the show’s psychotic Romeo, refers to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) to ‘justify’ his actions. The monster, he says – alluding to himself – is not really a monster; an old argument.

The Ted Bundy Tapes ends where Mindhunter begins: with the FBI’s methods of criminal profiling and pattern study in the late 1970s. By having serial killers supply the raw data of their murders, the FBI ‘built a composite of the mass killer and his victims’, as newscaster Tom Brokaw reported on the evening news in 1984. The establishment of a national centre of analysis of violent crime – which Mindhunter creator, Joe Penhall, refers to as a ‘death museum’ – allowed male FBI agents to figure out ‘who kills and why’ and, in Brokaw’s words, to ‘look for patterns in the methods of murders’ using interviews with notorious serial killers, including Charles Manson. (While the FBI employed female agents, the majority were overwhelmingly male.) Mindhunter is also built around the testimonies of real life-serial killers. In season one, Ed Kemper and Jerry Brudos recall the various humiliations they suffered at the hands of their so-called overbearing mothers (fathers are not mentioned). It would seem that women, along with feminism, drive men to kill women. The increase in the number of serial killers during the 1960s and ’70s, therefore, can be attributed – at least in part – to a feminist backlash enacted by men who felt emasculated by post-war America. In her book, Defending the Devil: My Story as Ted Bundy’s Last Lawyer (1994), attorney Polly Nelson writes: ‘It was the absolute misogyny of his crimes that stunned me,’ she wrote. ‘His manifest rage against women. He had no compassion at all [...] he was totally engrossed in the details. His murders were his life’s accomplishments.’

Mindhunter looks for reasons to corroborate motive while retroactively questioning that reasoning. It builds an epistemology around the psychology of serial murder in order to avoid addressing the lethal system of misogyny that produces it. The duality and duplicity that creates sociopathic masculinity puts it on the spectrum of artifice and psychosis, as Mindhunter illustrates through its young and increasingly morally culpable FBI profiler, Holden Ford. To its credit, the series does not separate normal masculinity from abnormal masculinity, federal agent from serial killer, the profile of the behaviour from the behaviour itself. Rather, it bonds and conflates them through a shared performance of masculinity. Both the profiler and the killer engage in the act of normality, or what David Sims – in a 13 November 2017 article about C.K. in The Atlantic – describes as ‘performing self-awareness’. In the case of sociopathic masculinity, normality is often the public act of self-awareness that subsidizes the private psychosis of misogyny.

Where male-centred dramas like Mindhunter and The Ted Bundy Tapes fail, and a feminist series like BBC’s crime series Happy Valley succeeds, is in the antiquated pursuit of motive and the study of ‘abnormal’ masculinity using psychological profiles designed by men. Happy Valley, which stars a female lead, and is written and produced by women, understands that patriarchy is a total system which houses all masculinity, and that misogyny itself is a principal psychology which is both aberrant and prescriptive. The forensics of motive, therefore, become redundant. Even Bundy himself dismissed it – claiming it didn’t ultimately matter. Men don’t need a reason to kill women, Happy Valley tells us: they need a reason not to. Moreover, men can kill women off – both literally and symbolically – in lieu of what actually restricts and displaces their authority. In Bundy’s case, the executioner was reportedly a woman.

In David Fincher’s Gen X Fight Club (1999), the narrator’s emboldened alter ego, Tyler Durden (also murderous), bitterly seethes about post-war feminization: ‘We’re a generation of men raised by women. I’m wondering if another woman is really the answer we need.’ In the age of Me Too and Time’s Up, the serial killer revival, in movies and on TV, hints at a troubling resurgence of the psychosexual male panic that led to the rise of the serial killer in the 1960s and ’70s. Perhaps, as with any distress, especially the kind sutured into our everyday lives, we need to keep replaying the banal horrors of masculinity in order to figure out how to finally wake up from its nightmare.

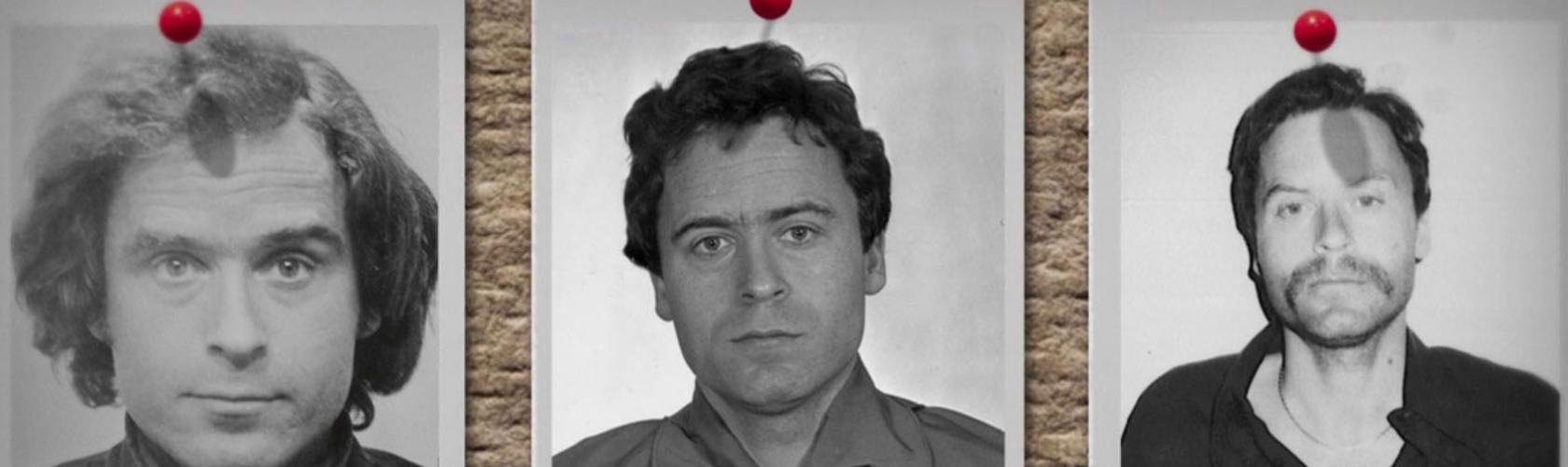

Main image: Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, 2019, film still. Courtesy: Netflix