Safety in Numbers?

Algorithms, Big Data and surveillance: what’s the response, and responsibility, of art? Jörg Heiser asked seven artists, writers and academics to reflect.

Algorithms, Big Data and surveillance: what’s the response, and responsibility, of art? Jörg Heiser asked seven artists, writers and academics to reflect.

Trevor Paglen

Trevor Paglen is an artist.

Something fundamental is changing in the world of images, and in the landscape of seeing more generally. We are at the point (actually, probably long past) where the majority of the world’s images are made by-machines-for-machines. In this new age, robot-eyes, seeing-algorithms and imaging-machines are the rule, and seeing with the meat-eyes of our human bodies is increasingly the exception.

Machines-seeing-for-machines is a ubiquitous phenomenon, encompassing everything from infrared qr-code readers at supermarket check-outs to the Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras on police cars and urban intersections; facial-recognition systems conduct automated biometric surveillance at airports, while department stores intercept customers’ mobile-phone pings, creating intricate maps of movements through the aisles. Beyond that, the archives of Facebook and Instagram hold hundreds of billions of photographs, which are trawled by sophisticated algorithms searching for clues about the behaviours and tastes of the people and scenes depicted in them. But all of this seeing, all of these images, are essentially invisible to human eyes. These images aren’t meant for us: they’re meant to do things in the world; human eyes aren’t in the loop.

All of this is new. Although Guy Debord’s spectacle society has certainly not gone anywhere, the advent of ‘operationalized’ images is upon us. The 21st-century landscape of images and seeing-machines directly intervenes in the surrounding world. Seeing-machines do things-in-the-world not through the subtle ideologies of visual mythmaking and fetishism, but through quantification, tracking, targeting and prediction.

How do we begin to think about the implications on societies at large of this world of machine-seeing and invisible images? Conventional visual theory is useless to an understanding of machine-seeing and its unseen image-landscapes. As for art, I don’t quite know, but I have a feeling that those of us who are interested in visual literacy will need to spend some time learning and thinking about how machines see images through unhuman eyes, and train ourselves to see like them. To do this, we will probably have to leave our human eyes behind. A paradox ensues: for those of us still trying to see with our meat-eyes, art works inhabiting the world of machine-seeing might not look like anything at all.

Laura Poitras

Laura Poitras is a filmmaker and journalist. She is currently reporting on NSA abuses disclosed to her by Edward Snowden, and editing the final instalment in a trilogy of films about post-9/11 America that will focus on surveillance.

In a top-secret strategy paper published by The New York Times in November, the US National Security Agency (NSA) describes its current surveillance powers as ‘The Golden Age’1 of signals intelligence. This ‘Golden Age’ is one where our past is recorded and digitally stored and our future is predicted. It is a system that seeks to know our friends and networks, physical location, biometric data and what we read and write. It is a system with ‘selectors’ and algorithms that watch our private communications moving across the internet to build graphs which identify us as ‘targets’ for further, more invasive, forms of surveillance. Its goal is the ‘mastery’ of global communications.

This document and thousands more disclosed by Edward Snowden reveal a fundamental threat to freedom.

As George Orwell and Michel Foucault both noted, one of the goals of surveillance is to get inside our heads. They don’t have to be watching – we just need to imagine they are. Every time we think twice before entering a search term, distance ourselves from a person or topic that might be targeted or censor our words, they win.

Surveillance targets our ability to think, create and associate freely. When I sat down to write this, I disconnected my computer from the internet to avoid my writing – the private process of formulating ideas on a page – being monitored.

As surveillance powers expand, so will the circle of people and activities monitored. I have no doubt we will see an increase of surveillance-themed art work, but that misses the larger point. Snowden not only revealed vast secret surveillance programmes, he revealed state control and the power of the individual to resist it. Artists can respond by doing work that resists control and conformity wherever it is encountered.

Our responsibility as citizens is to make sure the next generation does not have to censor its thoughts, actions and imaginations.

1 ‘A Strategy for Surveillance Powers’, The New York Times, 23 November 2013.

Jordan Ellenberg

Jordan Ellenberg is Professor of Mathematics at the University of Wisconsin, USA. He is a regular columnist for Slate and his book How Not to Be Wrong (Penguin, 2014) is forthcoming.

In the current moment, we are experiencing a sense of being tracked and measured by a cabal of machines whose genius is to distil the particulars of our lives into a substance called ‘data’. The machines (and by extension their handlers) then use this data to make inferences about our behaviour, our associations and our beliefs – information that we haven’t intentionally revealed or which we perhaps don’t even have access to ourselves.

Spooky, right? And seemingly antipodal to the kind of insight that art is supposed to provide: mechanical where art is human, repetitive where art is inventive. The machines that watch us can seem like H.G. Wells’s Martians: ‘minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic’ which peer down at the aggregate trail we leave in the informational substrate, and thus at us, ‘as a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water’.

But what machines do with data is not so foreign. It appears foreign, because when we talk about data we do so in the language of mathematics: loss functions and kernels, logistic regression and Greek letters. The language presents the same kind of difficulty for outsiders as the international art-speak found on museum wall texts.

Quantitative surveillance has two main goals: to classify and, having classified, to predict. And prediction comes down to this: people are likely to do things in the future that people like them did in the past. This principle – that we have tendencies, which are not inescapable but which take some work or some luck to escape – is not the property of mathematicians. How would novels function without it?

And the project of classification – which is to say all the work that’s hidden in the word ‘like’ or the phrase ‘people like them’ – is nothing more than the project of analogy, which asks us to set aside the boring observation that no two human beings (and, likewise, no two moments in time, no two societies etc.) are identical to each other, and replace it with a suite of more interesting questions, such as: in the space of human beings, which people are near each other? Or, when are two things alike, in ways beyond the obvious ones? That, of course, is a traditional artistic project too.

Big Data, automated behaviour prediction and classification relate to traditional art forms as photography does to drawing and painting. Photography isn’t there to replace artistic representation; in some of its manifestations it’s a new form of artistic representation, and in all its forms it’s something art can talk about, without acquiring expertise in photoreactive chemistry or digital compression algorithms. It will be the same story here.

And if you regard surveillance as a thing to be resisted, take some comfort from the fact that Wells’s Martians were eventually felled by terrestrial microorganisms. They were different from us on the surface. But on the inside, where they were vulnerable, they were built much as we are.

Sarah Hromack

Sarah Hromack is Director of Digital Media at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, USA. She also teaches at New York University’s Steinhardt School.

One of art’s most timeless functions lies in its ability to reflect the social and political conditions of its production in a way that renders those conditions newly intelligible. In the 1960s, conceptualism sanctioned quantification as a viable means of defining the form of art: measuring the parameters of an experience or a subject in stark, numerical terms was a seemingly agnostic way of making it known.

Today, the practice of quantification governs the everyday lives of everyday citizens. We are defined by data – or, to put it more accurately, we allow ourselves to be defined this way by willingly tracking and disclosing our own personal information through various digital channels. Now more than ever, data is used as a tool of power and control, a fact proven through the recent actions of Edward Snowden, Private Chelsea Manning, WikiLeaks, Anonymous and other individuals and organizations whose collective efforts have ushered in a new order within the public sphere.

In this context, does art made in or for the digital environment bear a given responsibility? I would argue that it does. Net art evolved in the 1990s through the advent and rise of social media to the present ‘post-internet’ moment, which describes digital practices in a much broader set of ‘real life’ terms. You no longer need to be able to write code in order to make art on (or, rather, for) the internet: the slickly designed, insidiously simple interfaces that mediate our workaday interactions invite every user to become a ‘maker’. The most compelling digital gestures aren’t those that merely document or represent this practical shift in images or words – my eyes have grown tired of the Tumblr or Instagram account-as-art-form – but those that suggest or even force an active form of personal engagement.

One example that I keep returning to when thinking about ‘active’ versus ‘passive’ digital engagement is occupyhere.org, designed and main-tained by developer and artist Dan Phiffer since October 2011. Initially built to support public conversations happening at the time in New York’s Zuccotti Park, the project has now morphed into a distributed network of wi-fi locations built to serve those in its immediate vicinity, who may exchange messages on its locally hosted website. Transient by design (and therefore inherently resistant to surveillance), occupyhere.org takes a refreshingly clear position for internet autonomy – one that only becomes more relevant as time passes.

Martha Rosler

Martha Rosler is an artist whose work centres on the public sphere and landscapes of everyday life, especially as they affect women. Her exhibition ‘Guide to the Perplexed: How to Succeed in the New Poland’ is currently at the Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, Poland, until 18 May. She lives and works in New York, USA.

Quantification, part of the rationalization of the world picture, is an essential bureaucratic tool. Its intricate embrace assumes a variety of guises, delineating – to pick a few signal examples – industry, geography and real estate, and population flows. By the mid-19th century, police metrics had converted trackers’ spoor into data. Policing was aided by photography, which also facilitated workplace surveillance regulating labour and employment, as well as anthropometric data-crunching, and thus pseudo-scientific race theory eventually underpinning genocide.

Mid-20th-century artists, rediscovering Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic segmentation of the time–space continuum in the animal/human realm, injected the spirit of such segmentation into the necessary demythification of the artistic paradigm. But quantification has also been naturalized elsewhere. The humanities, from philosophy to the social sciences, are pushed into defensive decline as numerical measures that mimic inexorable laws gain favour: mass-culture success (for example) rank-ordered by ‘audience share’; sports figures judged by their ‘stats’; pupil achievement assessed on the basis of machine-graded tests. For the state, statistical arguments dance with moral ones on how to regulate the poor. Middle-class data obsessions encompass the possibility of demented, continuous self-measurement by smartphones synchronized with your other devices. You can replicate your world or measure your game prowess in a myriad of digital ways.

Or, in this biopolitical era, you can worry over the US’s brain initiative (or the EU’s Human Brain Project); this intensive effort to ‘map’ the brain is half Pentagon-funded, for its intended uses begin with battlefield brain/machine ‘interfaces’. For the culture class, brain mapping is also implicated in the technicalization of aesthetic reception (see ‘neuroaesthetics’, a field invented by the well-funded Professor Semir Zeki of University College, London, who chortles over his threat to one day up-end the art market with foreknowledge of what kind of art is the most appealing) – and dabbled in by the ubiquitous Marina Abramović. Technicalization of aesthetic production, startlingly, is carried forward in a pair of Stanford English Department offshoots, the Center for the Study of the Novel and the Stanford Literary Lab, both of them founded and led by Marxist scholar Franco Moretti.

Artists and others have pushed back against the data stranglehold, wet and dry, statistical and human, by addressing individual areas and whole fields of operation, détourning the data when possible. Data nets are at the beating heart of modern states, requiring intensive, long-term joint efforts in all fields to mount meaningful defences against their expanding, pernicious use. That is the definition of full-scale mobilization.

MERCEDES BUNZ

Mercedes Bunz lives in London, UK, and Lüneburg, Germany, where she is Director of the Hybrid Publishing Research Team at Leuphana University. Her book The Silent Revolution (2013) is published by Palgrave Macmillan.

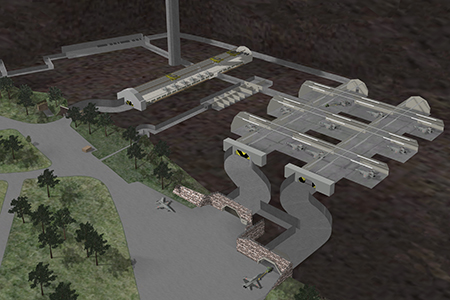

Code allows us to address, sort, filter and search for things. In my forthcoming book on algorithms, The Silent Revolution, I observe that code doesn’t just introduce new visual or sensory representations of society, but also establishes innovative ways of organizing it. First and foremost, code is transforming the world by introducing new modes of addressing it, as the Tumblr-aesthetic of Camille Henrot’s videos illustrates so brilliantly. Of course, this shift also has a massive impact on the procedures of power, on our societies and, consequently, on art. A good example of this might be the postmodernist tendency for artists to assume the role of their own artistic medium, enabling them to explore the social forces that run through a subject. Now the algorithmic power, its capacity to address and track, is affecting this very matter: the scandal of the NSA has made clear that the technique of Googling is also applied to humans, ‘finding’ all their (often very private or intimate) details and data. Is it a coincidence that this new form of ubiquitous surveillance was exposed in the same year that ‘selfie’ became the Oxford English Dictionary’s word of the year? The artist’s self-determined act of adopting the role of subject is no longer exceptional: the subject has turned into a public space. Art has responded by exploring this new visibility from all sides: think of James Bridle’s Surveillance Spaulder (2013), a wearable CCTV detector; Martha Rosler’s Theater of Drones, a public banner installation about drone warfare first displayed in 2013 in Charlottesville, Virginia (the first US city to have passed a law restricting the use of drones in its airspace); Christoph Wachter and Mathias Jud’s project Zone*Interdite (Restricted Zone, 2000–ongoing), for which they collect mass-media representations of military sites that are actually forbidden from being depicted; or Mishka Henner’s ‘No Man’s Land’ (2011–12), a series of images found on Google Street View that all happen to feature women standing isolated somewhere on the outskirts of southern European cities. Is it art’s responsibility to question our new algorithmic realities? In my opinion, art shouldn’t even have the responsibility to be irresponsible. In any case, rejecting the very notion of responsibility feels like the appropriate reaction to the transformation of our world according to the neoliberal logic of efficiency.

SHOSHANA ZUBOFF

Shoshana Zuboff is author of The Summons: Our Fight for the Soul of an Information Civilization (forthcoming) and In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power (1988). She is the Charles Edward Wilson Professor of Business Administration (retired) at the Harvard Business School, Boston, USA.

Edward Snowden’s revelations suggest that the NSA, once thought to be a secretive data-focused arm of us intelligence, has morphed into something else: a shadow regime impervious to geographic borders or political boundaries. It uses the capabilities loosely referred to as ‘Big Data’ to plunder the vast, ever-expanding digital surround and bring it to heel in the service of a perpetually receding goal: perfect knowledge.

The need to tame this surveillance empire now falls to all who love democracy. If we are to be effective, we need to grasp the origins and meaning of this global colossus. How do we locate its madness in the landscape of human experience? It’s a long conversation to which I offer an observation. It strikes me that there is one aspect of the human experience that is the precise inverse of the impulse toward Big Data and the will to omniscience. It is art; it is the artist.

The NSA and the artist are twin born, both summoned by the same terrifying void – the unknown and unknowable, the darkness and the silence. Google as we might, the revelations we seek lie just beyond our dancing fingertips.

Twin born, yes; but then separated to forge opposite paths. Art reveals that passage where terror is quelled through relationship. It murmurs: ‘Take my hand. We’ll go together. See, a candle!’ On this path, terror can be transfigured into the immaterial of what Anish Kapoor calls a ‘poetic existence’. We discover meanings that can sustain us with the grace and courage to tolerate doubt.

Big Data promises to rid the world of that darkness, while the machines ceaselessly thrum and clang. In the search for meaning, data is like seawater to a traveller lost at sea. That thirst cannot be slaked by data, but this only drives the frenzied system to ever more gargantuan gulps as it spirals into insanity.

The NSA’s insatiable appetite for Big Data was triggered by terrorists. But it is fed daily by the dark, black-red terror that shapes the instinctual life of every human. Quoting NSA documents from 2012, The New York Times recently reported that the agency seeks the capability to acquire data from ‘anyone, anytime, anywhere’, aiming to ‘dramatically increase mastery of the global network’ with a ‘massive Internet mapping, analysis and exploration engine’ that can chart ‘any device, anywhere, all the time’.

There is a sense in these NSA documents of overwhelming anxiety provoked by blind spots, gaps and mysteries that multiply, cascade and overflow with every gulp of data. Can we protect ourselves from terrorists without succumbing to the terror? Can we muster the faith and courage for thoughtful doubt? This way, a candle!