Survey Shows Extent of Class Divide in Creative Industries

A new report suggests that women, people from working-class backgrounds and BAME workers all face significant exclusion

A new report suggests that women, people from working-class backgrounds and BAME workers all face significant exclusion

Whom are the arts really for? This is just one of the pressing questions to be asked with fresh urgency thanks to the publication today of a new report that suggests the creative industries in the UK might benefit from a long, hard look in the mirror.

As its title suggests, Panic! issues an urgent warning to those working in the UK’s cultural professions. Subtitled ‘Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries’, the report is billed as ‘the first sociological study on social mobility in the cultural industries.’ It paints a picture of an exclusive industry whose workforce is unrepresentative of the wider population – socially, politically, and demographically. ‘If you think the creative industries should speak for a nation or a community then this report raises big questions,’ says Dr David O’Brien, one of its three lead authors. Nonetheless, those involved are hopeful that their work will lead to overdue systemic change.

Panic! is the result of a partnership between Edinburgh College of Art, the University of Sheffield, and Create – an east London-based commissioning agency that encourages collaborations between artists and urban communities. The report is based on a survey of 2,487 culture professionals that was commissioned by Create in 2015. In addition, the report’s lead authors – Dr Orian Brook, Dr David O’Brien, and Dr Mark Taylor – have analyzed longer-term data from the British Social Attitudes Survey, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), and the Office for National Statistics. Despite the quantity of data analyzed, the report does not claim to be a comprehensive overview, but a vital snapshot.

What emerges is an account of ‘a “creative class” quite distinct from the rest of society.’The report strongly suggests that meritocracy is a myth. Women, people from working-class backgrounds, and Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) workers all face significant exclusions from an industry which is over-represented by upper middle-class white men. Just 2.7% of workers in museums, galleries and libraries are of BAME backgrounds (compared to nearly 10% of the UK workforce overall) while just 12.6% of workers in publishing are of working-class origins (compared to 35% of the workforce overall).

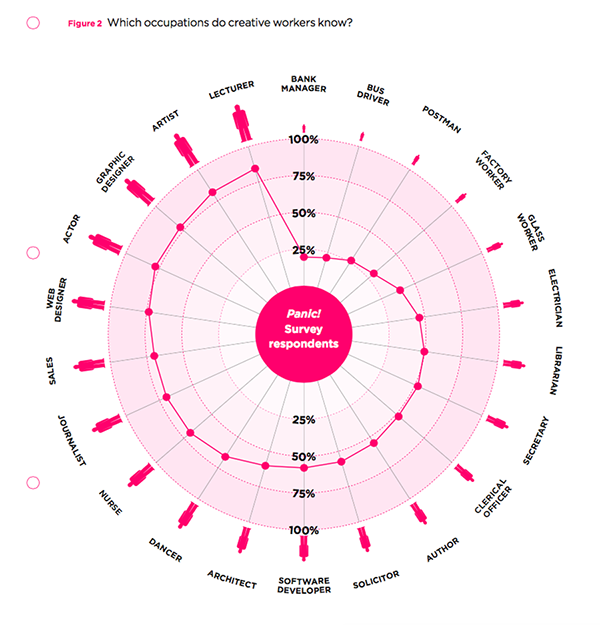

Although differences emerge within the sector, the overall picture is of a homogenous workforce whose social networks are largely limited to other culture professionals and whose values are markedly different to those of any other occupation. Cultural workers are ‘the most liberal, most pro-welfare and most left wing of any industry.’ These same descriptions apply both to makers of culture and consumers: culturalworkers attend four times as many cultural activities as people in working-class occupations. ‘Many in the sector really do have a distorted picture of just how unlikely it is for a working-class person to visit their institution,’ says Dr O’Brien. ‘Basically, you have a set of people who look very much like the audience that they are serving. We could consider the cultural sector a closed segment of society.’

Unfortunately, those in the best position to change the system are often unable to see the problem. Those at the top are most likely to think they got there simply through talent and hard work.‘Workforce inequalities are reinforced by the prevalence of unpaid labour,’ argue the report’s authors. Yet unpaid internships are on the rise (48% of people under 30 reported they had done an unpaid internship, compared to just 6% of respondents over 50) and working for free is described in the report as ‘endemic’.

What is perhaps especially surprising is that the current situation is not new. Although the report shows that there are more upper middle-class people working in the creative sector today than in 1981, Panic! apportions this to a result of wider changes to Britain’s class structure: there are simply more upper middle-class people overall.1 The chancesof a working-class person gaining a job in the arts are as low as ever. ‘It seems that there has never been a time when the arts reflected British society in an equitable way,’ says Hadrian Garrard, director of Create.

Although, at times, Panic! makes for grim reading, those responsible believe it can act as a catalyst for systemic changes. If the anger behind the recent gender pay gap reports is anything to go by, then the desire for large-scale changes to workplace practices is widespread. Certainly, the data presented in Panic! may well prove persuasive to those in positions of authority (the successful white men in thrall to the myth of meritocracy). Then, it is hoped that better, evidence-based decision-making will follow across the sector.

To this end, alongside the report is an accompanying cultural programme, including an event at the Barbican on 27 June and newly commissioned work by artist-activist Ellie Harrison. Looking close to home, Garrard says that Create has already begun to change its own recruitment policies on the back of the research. The emphasis is now on capabilities and potential more than experience and qualifications. ‘We're hopeful that Panic! could contribute towards a shift in thinking and practice,’ says Garrard. ‘For this to happen, it's important that we acknowledge the privilege in our own organizations and recognise that the arts are not, as things stand, representative of the population as a whole.’

1 Brook, O’Brien and Taylor, Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries, 2018, p. 18

Main image: Brook, O’Brien and Taylor, Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries, 2018