What Role Do Photographers Play in an Increasingly Automated Image Culture?

At the Photographers’ Gallery in London, a show examining the increasingly ubiquitous images produced by machines

At the Photographers’ Gallery in London, a show examining the increasingly ubiquitous images produced by machines

Who are photographs for? Who are photographs by? Increasingly, the answer to both questions is, more or less, machine: images are captured by autonomous, or semi-autonomous devices in the act of gathering data for artificial intelligences.

Reading the world of the internet through human eyes, this devolved, machinic image-capture seems ubiquitous. Whether tracking down a building through Street View, reading an academic text on Google Books or locating an artwork through a search engine, there is little sense of authorship to the photos we consume online. For all our sophisticated understanding of image manipulation – from Snapchat bunny filters to movie special effects – we are remarkably trusting of many of these apparently unauthored images, as if the question of intent or agenda was removed alongside human agency.

In ‘All I Know Is What’s On The Internet’ – an exhibition at London’s Photographers’ Gallery, ominously titled after a Donald Trump quote – artists mine online content for evidence of human intervention. These often present themselves as glitches of one form or another. Winnie Soon’s video Unerasable Images (2018) shows how heavy-handed censorship causes even a Lego rendering of the 1989 protests at Tiananmen Square in Beijing to pop in and out of visibility on online platforms in China.

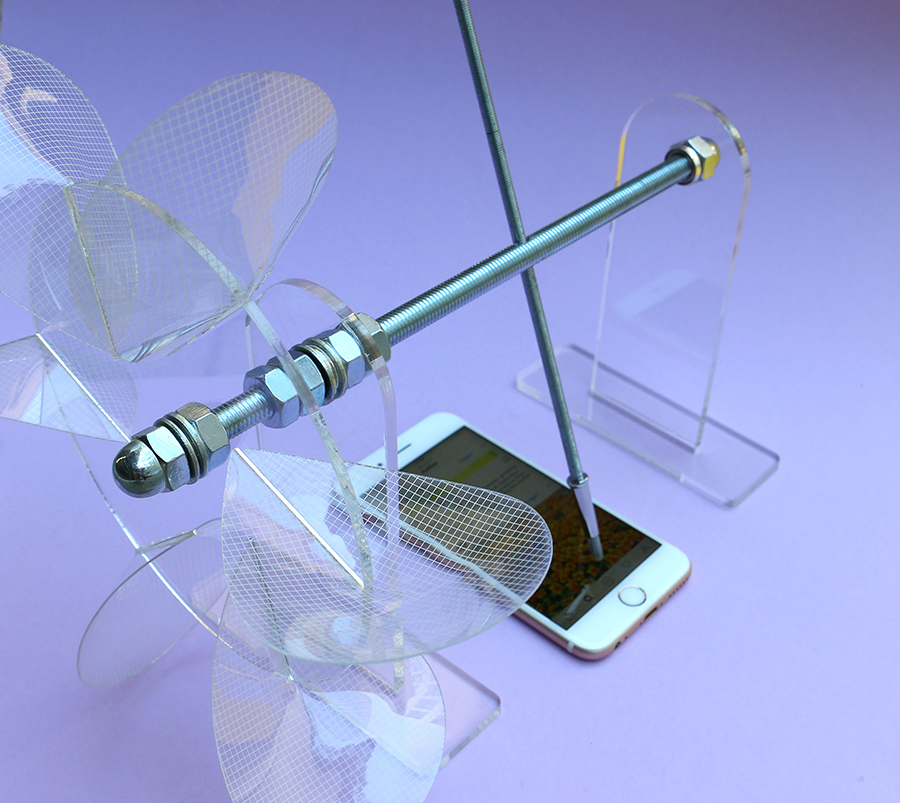

Andrew Norman Wilson’s Scanops prints (2012–ongoing) reproduce lone images found among Google’s Books pages that unwittingly reveal the role of human beings in the data extraction process. Fingers and hands wearing latex anti-contamination gloves are seen holding pages flat for scanning. A series of goofy, mangled, circular portraits by Emilio Vavarella – The Google Trilogy 3: The Driver and the Cameras(2012) – turn out to be accidental shots harvested from Google Streetview, capturing the drivers adjusting the cameras on their vehicles

Eva and Franco Mattes’s series Dark Content(2016) explores the covert role of content moderators – the humans performing the role of censors commonly attributed to algorithms – some working freelance for social media, others for the comments section of news sites. All participate in the videos anonymously, their voices and likenesses transferred to generic avatars. A moderator hired by a third party for a social media site worries that, after blocking a video containing child pornography, the censure might go no further. Will anyone help the child? Will the video be reported to the police? Caught in the web of the automated service economy, she can find no way of contacting the client company to check. Moderators for the news sites are horribly disturbed by suicide videos, and likewise haunted by unanswerable questions about how the footage made its way to them online.

Sebastian Schmieg and Silvio Lorusso’s suite of leporellos Five Years of Captured Captchas (2017) are a reminder that more often than we realize, the humans caught in that web are us. ‘Captcha’ puzzles (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) used on online forms serve a double function: having identified us as non-robot, we are offered text or images that are troubling the optical character recognition tasked with digitizing them. Unbeknownst to us, our human eyes and brain become harvesting tools for non-human intelligence.

The artists point out that Google was once slapped with an (unsuccessful) class action lawsuit for this unpaid labour. The ethics are certainly twisty. On the one hand, what harm is there in crowdsourcing interpretation of documents and images that become sources of public information? On the other, if they are the property of Google – a global for-profit company that extends its post-national stance to its attitude to taxation – how public are they, really? And why do it covertly?

This vision of humankind as sentient servants of a giant artificial intelligence is extended in Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon’s World Brain (2015). A feature-length film work split between scenes in giant data centres, and a neo-survivalist forest camp populated by tech intellectuals, World Brain suggests that external observers of our present earth would see a planet colonized by a super brain that we are collectively dedicated to nurturing. The internet is presented as a highly successful superorganism, within which we all live, both virtually – the details of our day-to-day captured as data – and physically, surrounded by the cables, wires and transmissions of its infrastructure.

While not directly referenced in the exhibition, the spirit of James Bridle’s recent book The New Dark Age hovers over ‘All I Know …’ The exhibition brings illustrative focus to many of the issues raised by Bridle. The visual economy with which these works raise complex questions about control, surveillance, trauma, manipulation and agency is, in itself, a sharp reminder of the power of the image in relation to the word.

If an artificial intelligence learns what kinds of pictures you favour, why should it not assist you in optimizing photographs of your family? If an algorithm can predict what pleases you in an image feed, why should it not boost your happiness by showing you more of them? If cameraphones are already ubiquitous in conflict zones, why do we need war photographers? If we’re already broadcasting ourselves all of the time, what’s the point of documentary filmmakers? Is it wrong to have content moderators removing images intended to traumatise us? For the Photographers’ Gallery – an institution hitherto dedicated to images transmitting the vision of one human eye to another – these enquiries are pressing. They carry in their wake deeper questions about who a ‘photographer’ is, and what their role might be in an increasingly automated image culture.

‘All I Know Is What’s On The Internet’ runs at the The Photographers’ Gallery, London until 24 February 2019.

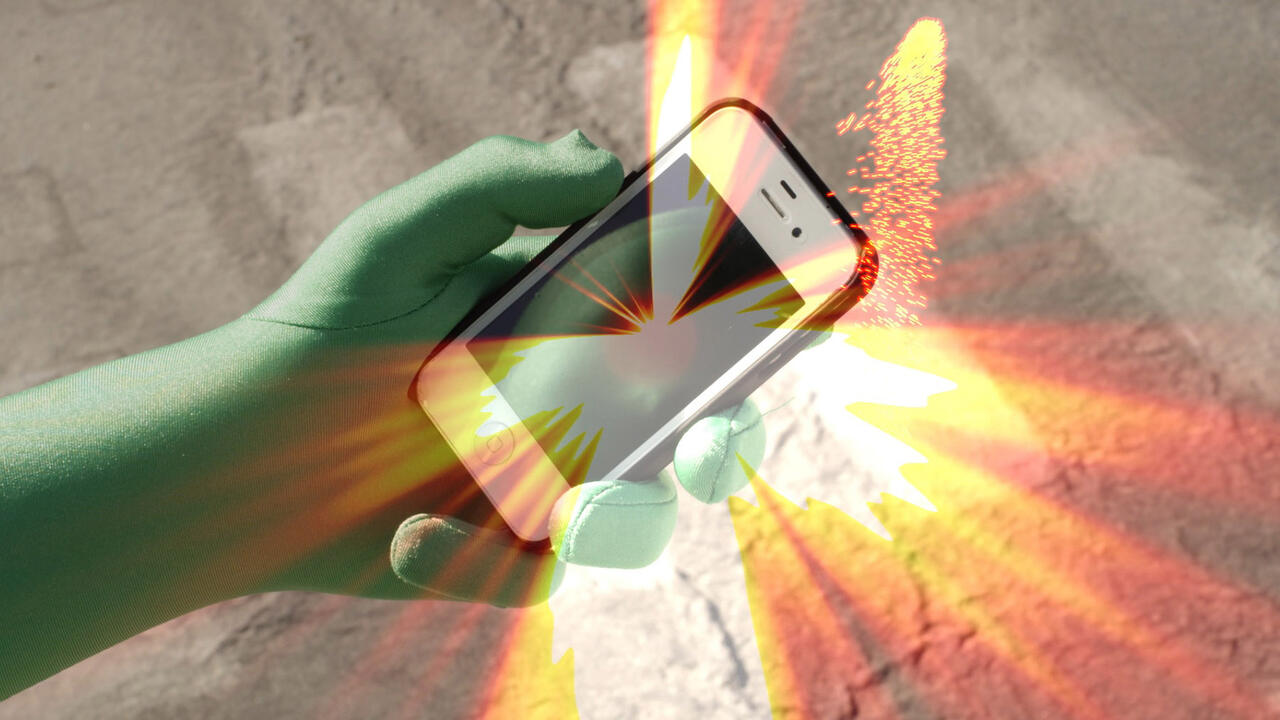

Main image: Miao Ying Lan, Love Poem, 2014-15. Courtesy: The Photographers’ Gallery, London