What MoMA’s ‘Björk’ Exhibition Reveals About the Uneasy Relationship Between Museums and Music

‘So shallow is this show that I left with the surprising sensation of knowing even less about Björk than I did when I entered’

‘So shallow is this show that I left with the surprising sensation of knowing even less about Björk than I did when I entered’

By now, I imagine, you will have read the withering reviews of ‘Björk’, the musician’s ‘mid-career retrospective’ at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the paranoid amongst you would be forgiven for suspecting the show to be a fiendish plot by fusty old men to finally prove that pop music has no place inside art’s big castle on the hill. You will have heard about the exhibition’s cramped rooms and the half-hearted arrangements of notebooks and outfits hung on creepy waxworks of the Icelandic singer. You will have learned that there is an icky fairy tale disguised as an audio guide for the show. You will also know that the exhibition has absolutely zilch to say about how Björk’s collaborations with designers and film directors have evolved, or how her music is written. So shallow is this show that I left with the surprising sensation of knowing even less about Björk than I did when I entered. Truly, I have to take my hat off to MoMA, because it must take a great deal of effort for an institution famed across the world for its scholarship in the field of modern and contemporary art to produce an exhibition as vapid as this about a genuinely interesting artist.

Conceived and organized by Klaus Biesenbach – MoMA’s Chief Curator at Large and Director of MoMA PS1 – and, according to the marketing blurb, ‘the product of a close collaboration’ with Björk, this exhibition is just the latest manifestation of the conflicted relationship art museums have with pop music. But can we blame them for being wary? They’re museums of art, after all, not music. However, the story of postwar 20th-century art is as inseparable from the story of pop music as it is from its closer cousins in architecture, design and cinema. Yet still – still – major institutions such as MoMA rend their garments in torturous doubt over its worth.

In his catalogue essay for ‘Björk’, Biesenbach writes as if it’s 1955. He explains how the exhibition ‘aimed to broaden the canon of what contemporary museums exhibit and collect, while also raising questions about the longevity of pop music, a genre that is evolving and has not proven its classic timelessness’. He goes on to ask: ‘Can a work of popular culture achieve “eternal truth and beauty” when it is independent and removed from its broader cultural context?’ The same question could easily be asked of most contemporary art. Many achievements in pop music, regarded today by millions of people as serious cultural landmarks, are just as old as some of the canonical works on display at MoMA. Take, for instance, the most ubiquitous of all ‘art rock’ albums, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band by The Beatles. Released in 1967 with a sleeve design by the artists Peter Blake and Jann Howarth, it is contemporaneous with the first key works of minimalism and pre-dates swathes of conceptual and postmodern art. I would have serious misgivings about the cultural literacy of any curator who thinks the jury’s still out on The Beatles but gives a free pass into ‘eternal truth and beauty’ for some milled-steel abstract sculptures from the 1970s in MoMA’s collection.

Perhaps MoMA’s failure to make anything of ‘Björk’ is a question of institutional comfort zones: art museums lack an effective formal exhibition language with which to represent pop music, and the staff expertise with which to adequately parse it. (Biesenbach curated Björk’s show as a fan, not a scholar: a fact thrown into sharp relief in the exhibition catalogue with informed essays by critic Alex Ross and musicologist Nicola Dibben – the only intellectual moments in the entire endeavour.) Despite having excellent departments for design, architecture and film, MoMA, in many people’s minds still represents high-modernist painting and sculpture.

‘Björk’ is divided into two sections: an exhibition of objects titled ‘Songlines’ and two cinema spaces. ‘Songlines’ is structured chronologically around each of Björk’s solo recordings (editing out her work in 1980s Iceland with post-punk bands Kukl, The Sugarcubes and Tappi Tíkarrass). Its audio guide is written by the poet and novelist Sjón. Titled ‘Triumphs of a Heart: A Psychographic [sic] Journey Through the First Seven Albums of Björk’, it begins by telling us that ‘once there was a girl […] who lived alone in a lava field’ and ‘the heart she sheltered in her breast was her companion’. It slushes on like this from start to finish, saying nothing about Björk’s work, but oodles about how ‘there is only matter […] only movement […] only matter and movement’. Throughout, Sjón insists on referring to Björk as either a ‘girl’ or a ‘mother-girl’, as if in her 49 years she has never had agency as an adult. Can you imagine a museum retrospective of a middle-aged male artist referring to him as a ‘boy’?

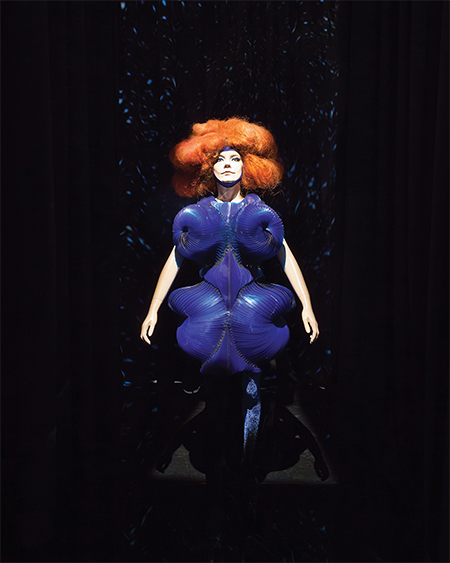

One cinema shows Black Lake (2015), a music video by Andrew Thomas Huang, the award-winning director behind films for Atoms for Peace and Sigur Rós, amongst others. Specially commissioned by MoMA and set to a track from Björk’s new album, Vulnicura (2015), Black Lake is described as a ‘sound and video installation’, although what the argument is for defining it as installation art rather than a good old-fashioned music video is impossible to fathom. It plays across two screens and uses a stormy Icelandic backdrop against which Björk emotes heartache in a variety of outfits. Digitally rendered blue lava flows through volcanic fissures as Björk sings of her ‘soul torn apart’ and of how her ‘spirit is broken’. It’s a song of raw feelings but a pedestrian video – certainly in comparison to the cycle of music videos dating back to Björk’s solo album Debut (1993), which is shown in the adjacent cinema.

I first heard Björk in 1988, when The Sugarcubes’ single ‘Birthday’ was released in the UK. Her voice sounded singularly fresh, as did her combinations of house music and ECM-style jazz on Debut. It wasn’t until I later discovered musicians such as Joan La Barbara, Meredith Monk and Yoko Ono that I was able to connect the startling range and textural invention in Björk’s voice to broader historical currents. The great disservice MoMA does to Björk is in failing to contextualize her work at all. Björk’s career encompasses pop music’s last significant period of blazing innovation – the 1990s – and now navigates its 21st-century uncertainties. Her work ties the history of music in post-independence Iceland to the class warfare of anarcho-punk in Thatcher’s Britain. (Politically radical British band Crass released records by Björk’s group Kukl.) This narrative includes the post-acid house revolutions in European youth subcultures and, from there, explodes across the world into design, filmmaking and contemporary art. It provides a way of looking at collaboration across the creative disciplines, through major designers – Hussein Chalayan, Alexander McQueen, M/M (Paris), and Bernhard Willhelm – photographers such as Nan Goldin, Nick Knight, Glen Luchford, Stéphane Sédnaoui and Juergen Teller, and filmmakers as diverse as Björk’s ex-partner Matthew Barney, Chris Cunningham, Michael Gondry, Spike Jonze and Lars von Trier. As for her legion of musical alliances, Björk pulls from most far-flung corners of the sonic universe, from Icelandic folk musicians to British classical composers, from Inuit throat singers to US hip-hop producers and Malian kora players. She touches on music education, too: her Biophilia Educational Project was developed with the City of Reykjavik and the University of Iceland, using technology to nurture children’s musical creativity and their appreciation of the natural sciences. The instruments custom-built for 2011’s Biophilia album – exhibited in the MoMA lobby, although the wall texts leave you clueless about their workings – are part of an historical lineage that includes John Cage, Maurice Martenot, Harry Partch, Luigi Russolo, Pierre Schaefer and Léon Theremin.

This exhibition opened on the heels of Vulnicura. Chronicling her break-up with Barney, the album is an intimate set of songs, orchestrated with a consistent palette of mournful strings and beats paced like feet dragging sadly along the ground. Emotionally unvarnished, the technical inventiveness demonstrated on Biophilia is largely absent, making way for a pop album about broken hearts much like any other. Walking around her exhibition, you can practically feel the museum blushing at the earnestness of songs about acting spontaneously, declaring passionate love, nurturing children or caring for the environment. These are not subjects that sit comfortably within the behavioural conventions of contemporary art; cool, critical distance, not messy human feelings, is still the mother tongue for art museums. At MoMA this friction is poignant and pointed. On the wall of the museum’s atrium is a huge projection of the video for Björk’s 1993 track ‘Big Time Sensuality’, a song about excitement at the unknown potential of a new relationship. The video depicts her dancing on the back of a flatbed truck driving through New York, but is shown here in silence, washed-out by light: Björk’s unselfconscious fun symbolically effaced by the institution. This is the real truth the exhibition raises: MoMA is confused about its feelings.