Pope.L Has Never Been More Urgent

Can a trio of exhibitions in New York shed light on this enigmatic figure?

Can a trio of exhibitions in New York shed light on this enigmatic figure?

Pope.L’s Du Bois Machine (2013) is a three-metre wooden sculpture of a man’s legs, positioned upside down on a table, from which emanates a recording of a young girl recounting an intriguing tale. Her monologue chronicles a true story: in the late 1990s, the artist received an envelope containing hair, skin and dirt allegedly belonging to Martin Luther King, Jr. The recording tells of Pope.L’s subsequent attempts to develop a project that would disperse this bodily material: posters printed with the text ‘This is a painting of Martin Luther King’s penis from inside my father’s vagina’; an encounter with a Black man on a bus; and a blog (distributingmartin) tracking the artist’s experimental dispersal efforts.

Presented as part of a 2013 exhibition at The Renaissance Society in Chicago, Du Bois Machine embodied the magnitude of W.E.B. Du Bois, who, like King, seemed, in the words of the recording: ‘to be able to contain, as it were, an incredibly large and complex family of desires, actions, objects and images seemingly merely within the stride of his legs’. In a curious meld of language, storytelling and humour, Pope.L attempts to give space to that which lives between our understandings of a person, their body and the stretch of their shadow.

Since the late 1970s, Pope.L has worked in performance, video, drawing, installation, sculpture and teaching, troubling facile readings of the machinations that govern the relationships between race, labour, capitalism and materiality. His practice traverses genres in an attempt to reckon with everything from the tenuousness of Black masculinity in public space to the lingering economic effects of post-industrial America. What he offers is a framework through which – to quote again from the Du Bois Machine monologue – you ‘get to play in the hinges’: to look more critically, in other words, at an ever-evolving set of social, material and political consequences of racism, rampant consumerism and environmental injustices.

Given the current political situation, however, is it still enough for artists merely to expose these hinges? Or, as society reconciles with its demons, should artists be providing us with answers or with pathways toward solutions? As critic and curator Aria Dean wrote in her review of the 2019 Whitney Biennial: ‘What are the conditions of art today? They aren’t what they used to be, and we need a language for what they are.’1 Dean writes with specific regard to the flare-up that surrounded the museum’s former board vice chairman, Warren B. Kanders, CEO of the US-based weapons manufacturer Safariland. A cloud of protest quickly surrounded the biennial as news of Kanders’s position became public. (He had been on the museum board for years, but it was recently exposed that Safariland teargas was used at the US-Mexico border.) More than this, however, Dean asks the critical question: ‘What can art do?’ Even as her inquiry points to the relationship between art-making and what could be understood as ‘dirty money’, it might do well to pay close attention to the language she provides through her question, since it can be read as a broader proposition for the politics of cultural production.

Pope.L, it would seem, understands his work less as a container for some sort of radical shift in the world itself, and more as a site through which interrogations are formed that might then be carried beyond his work and into the world, leading to affirmative change. ‘It’s not that I have the arrogance to believe that I know what should be done,’ he told Martha Wilson in a 1996 BOMB Magazine interview. ‘In fact, I’m afraid of the responsibility, but something should be done. And if I can construct works that allow people to enter themselves, thus, enter the mess – then it’s a collaboration and maybe, possibly, who knows, why not – I’ve nudged something.’

This offers a lens through which to consider the artist’s 2017 installation and performance, Flint Water Project. The project evolved as a response to the massive health crisis that began in 2014, when the US state of Michigan decided to save money by switching the water supply for the majority Black city of Flint from Lake Huron to Flint River. The city, however, did not take up recommendations to treat the river water and, shortly after the switch, it became clear that the river was contaminated with high levels of lead and bacteria, such as E. coli and legionella. By early 2015, in the aftermath of the significant corrosion of the city’s water pipes, residents of all ages became severely sick as Flint began to experience an outbreak of legionnaires’ disease. In October of that year, then-Governor Rick Snyder made the decision to switch Flint’s water source back to Lake Huron, but government officials remained evasive about their lack of precaution and delay in resolving the situation. Local and national campaigners, who from the outset had rightfully identified the culprit as environmental racism, continued to push for transparency and accountability. It was not until January 2016 that an emergency order was issued by the Environmental Protection Agency.

By the time What Pipeline, a Detroit-based gallery, invited Pope.L to create a response, Flint’s crisis had been ongoing for three years. However, rather than stage an exhibition in Detroit, the artist proposed his Flint Water Project as a way to avoid ‘revictimizing’ the city, in the words of the project’s Kickstarter page. Created by the gallery and the artist, the page queries further: ‘What if Detroit could be the hero and come to the rescue of another Midwest city in need?’ Under this rubric, contaminated Flint tap water was bottled, packaged and sold as a limited edition at What Pipeline, which had been transformed into a shop and crisis information centre to raise awareness about the tragic neglect. Sales proceeds were donated to the non-profit organizations Hydrate Detroit and the United Way of Genesee County.

This autumn, Pope.L returns to the theme of water with a new work, Choir (2019), on the occasion of his complementary exhibitions in New York, ‘Instigation, Aspiration, Perspiration’, held across three institutions: Public Art Fund, the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Choir, on view at the Whitney, is a public, immersive sound and sculptural installation that features an upside-down fountain from which 800 gallons of water will flow into a tank, to a soundtrack of a 1930s Black work song and white choirs singing Black spirituals. Choir argues for the water fountain as an important site of ‘congregation’, as curator Christopher Lew commented to The New York Times. Such a congregation is not a neutral one, since it is also deeply embedded within the legacy of segregation and the Jim Crow South. How, and to what end, might meaning be scrambled or ascribed to such a symbol in the context of this new setting?

Pope.L has often pushed back against a reading of the centrality of race within his practice. ‘Some critics have written about my work in the past’, he observes in the essay ‘Some Notes on the Ocean’ (2005), ‘and have construed my project to primarily focus on race or blackness or a sociology of such … Hmmm.’2 For the artist, the notion or expectation that he deliver a singular grandiose point about Blackness is not just impossible: it is also absurd. Just what should a Black artist be doing or saying? On the other hand, it is impossible to assess the canon of contemporary (American) performance art without paying particular attention to Pope.L’s use of the body – often his own – and its consequences for a study in Blackness.

For other Black avant-garde artists from the US – including Sherman Fleming, Ulysses Jenkins, Lorraine O’Grady and (before she retired from being Black) Adrian Piper – who emerged alongside Pope.L in the 1970s and ’80s, performance was a site of socio-political critique, even as it functioned as a self-contained somatic language: a feedback loop of Black movement, expression, speech and idiosyncrasies. In Times Square Crawl a.k.a. Meditation Square Pieces (1978), Pope.L traverses the maddeningly clogged Manhattan tourist spot on his hands and knees, wearing a suit and dress shoes, in front of bemused onlookers, while a policeman attempts to get him to stand up. This was the first of his ‘Crawl’ performance series, of which there have been more than 40, including Tompkins Square Crawl (1991) and The Great White Way, 22 Miles, 9 Years, 1 Street (2001–09). For the latter, Pope.L wears a superman costume, attaching a skateboard to his back in lieu of a cape, with the intention of crawling the entire length of a New York street, but only moving, with each iteration, for as long and as far as his body allows. The crawls are gruelling, sweaty, painful endeavours in which his (Black) body is on display for the many spectators who gather to watch.

The crawls also become an avenue to think through conditions of exclusion and inclusion. Or, rather, who gets to belong and why? These are exercises of endurance and exhaustion that trouble anxieties about non-white subject positions within public space, critiquing, to a certain extent at least, an Enlightenment or modernist proposition of universality.

During his Tompkins Square Crawl in New York’s East Village, Pope.L was approached by a Black man, also wearing a suit, who was angered by the performance. ‘You make me look like a jerk!’ he screams at Pope.L, in footage of the incident. Yet, the artist is only too aware of what those he has termed ‘less-blacks’, and white people in particular, are thinking: that Black male bodies are persistently noted as absent even when they are present.3 This absence is not devoid of value; rather, it is in constant negotiation with respect to the white male body. Consider ‘Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book’, Black feminist scholar Hortense Spillers’s 1987 article that offers a framework for thinking through the way that the (captive) Black body, in the aftermath of the transatlantic slave trade, lacks subjectivity and remains positioned as a perpetual biological and physical Other. Certainly, Pope.L recognizes the perception of the Black male body as a dangerous, sensual presence – both threat and intrigue – in a white world.

Just as pivotal to understanding the performance, however, is the horizontal position of the crawling body, through which Pope.L references the politics of labour. As curator Adrienne Edwards notes in her essay ‘The Will to Exhaust’ (2015): ‘From the very beginning, the crawls were conceived of as potential group performances’ or in the spirit of collaboration, as Pope.L stated in his interview with Wilson, implicating more than just himself and his body.4 That intention came to fruition in works such as Pull! (2013), commissioned by SPACES gallery in Cleveland, which served as a testament to the power of shared commitment by recruiting local volunteers to drag an ice-cream van 40 kilometres across town. As they did so, a screen on the back of the truck displayed images sent by people from across Cleveland, illustrating what work meant to them. Artists and teachers, caretakers and organizers: the ‘pullers’ were ordinary residents of a city like many others, deciphering a way forward in the midst of economic recovery.

What was it that drove Pope.L to recruit these ‘pullers’ to execute such a slow, taxing feat; to manually drag a truck that was, in fact, still operational? There is a danger in reading these performances as social practice – not only because the boundaries of that nebulous discipline shift widely and often, but because the artist has described himself as ‘more provocateur than activist’, as he called himself in the video work White Baby (1992). Rather, the significance of Pull! was inscribed by the very act of the group assembling daily to participate in this strenuous yet banal endeavour.

In his 2014 essay on Pope.L, ‘The Balloon Inside the Body’, artist and writer Nick Bastis characterizes this type of action as labour (distinct from work) in that no product accumulates or results: ‘Like caring for a child, tending to a garden or loving someone, [labour] needs to be constantly reproduced and defended because no monument or product accumulated from it can act as a stand in.’5 What does it mean, Pope.L wonders, to labour together in and through difference? There is no grand declaration; there is only what hinges between.

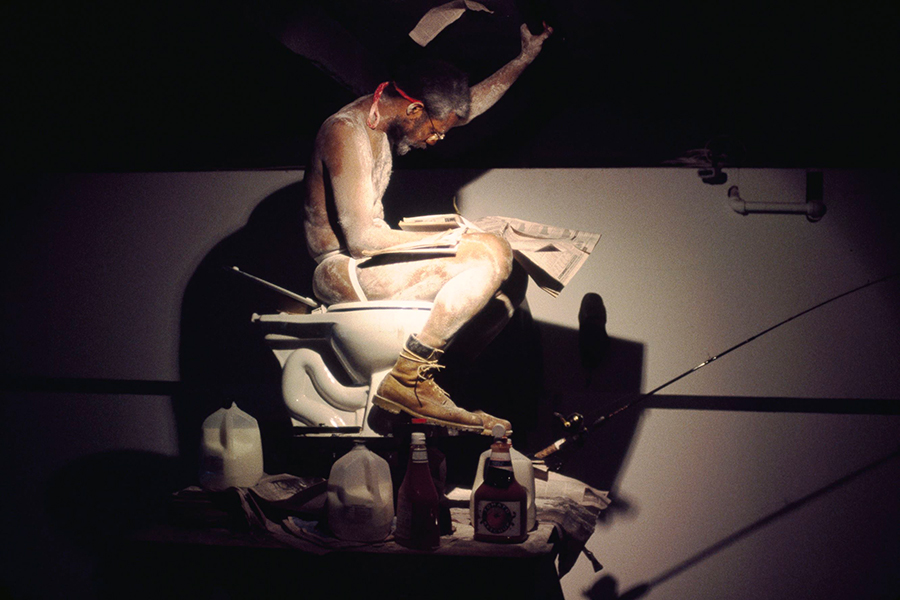

To navigate this ‘between’, Pope.L revels in the absurd: humour and exhaustion intersect as a type of poetics. Consider the artist’s series ‘Skin-Set Drawings’ (1997–ongoing), which pokes at the nature of the language used to describe race. Statements such as ‘YELLOW PEOPLE EAT THE WORD’, ‘BLACK PEOPLE ARE TAUT’ or ‘WHITE PEOPLE ARE ANGLES ON FIRE’ are written on ordinary sheets of paper as Pope.L emphasizes the flimsiness surrounding definitions and the textual configurations of racial categories. There is also the iterative work Eating the Wall Street Journal (1978–2001). For his restaging of this piece at New York’s SculptureCenter in 2000, Pope.L sat on a toilet – covered in flour, wearing only a jockstrap and glasses – reading excerpts from the paper, before dousing strips in ketchup and milk, chewing them up, then spitting them out, leaving the resulting muck on the floor for the duration of the exhibition. Eating the Wall Street Journal forces the audience to confront not merely the discomfort of excess and the grotesque detritus of a reputable news source but also makes a claim about the paper’s reverence to the capitalist system around which it centres: this, too, is muck.

In September, Pope.L realized what many have categorized as his most ambitious crawl, Conquest, organized by Public Art Fund as part of his trifecta of exhibitions. More than 140 crawlers began the feat from the West Village’s Seravalli playground, trekking north to Union Square, passing through the storied Washington Square Park along the way. In truth, the task remains just as daunting as when Pope.L undertook his first crawl, all alone, in a since much-changed New York. Yet, in ways, Conquest brings us back to the artist’s original inquiry: what would it mean to move together? What meanings might be nudged if we collectively enter the mess?

1 Aria Dean, ‘On Progress, or the speed at which a square wheel turns’, X-TRA Online, published 18 August 2019

2–3 Pope.L, ‘Some Notes on the Ocean’, in Some Things You Can Do with Blackness, 2005, Kenny Schachter Rove, London

4 Adrienne Edwards, ‘William Pope.L: The Will to Exhaust’, Spike, issue 45 (Autumn 2015), p. 119

5 Nick Bastis, ‘The Balloon Inside the Body’, in William Pope.L: Showing Up to Withhold, 2014, University of Chicago Press, p. 21

Conquest took place on 21 September 2019. ‘Choir’, Whitney Museum of American Art, and ‘member’, Museum of Modern Art, both New York, USA, close February 2020.

Main image: Pope.L, Conquest, 2019, performance documentation. Courtesy: © Pope.L and Public Art Fund, New York; photograph: Timothy Schenck

This article first appeared in frieze issue 207 with the headline ‘What Lies Beneath’.