Zineb Sedira’s Films Recreate Radical Political Alliances of the Past

Ahead of her presentation in the French Pavilion at this year's Venice Biennale, Zineb Sedira speaks with Róisín Tapponi about the influence of Third Worldist cinema and transnational alliances on her practice

Ahead of her presentation in the French Pavilion at this year's Venice Biennale, Zineb Sedira speaks with Róisín Tapponi about the influence of Third Worldist cinema and transnational alliances on her practice

Róisín Tapponi Can you tell me about Les rêves n’ont pas de titre [Dreams Have No Titles, 2022], your project for the French Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale?

Zineb Sedira There are various components, but the main one is a 16mm film, Les rêves n’ont pas de titre, exploring Third Worldist cinema: the militantly anticolonial, sometimes anticapitalist, films made in Algeria in collaboration with other countries following independence in 1962, which were often co-produced with international filmmakers like Costa-Gavras, Gillo Pontecorvo, Ettore Scola and Luchino Visconti. Rooted in a political agenda, films such as Michel Drach’s Élise ou la vraie vie [Elise or Real Life, 1970], about racism and the Algerian War, sought to establish ‘solidarities’ between countries. Some of the filmmakers, especially the Italians, were often members of the Communist Party, and interested in making anticolonial films. These co-productions with Algeria represent a moment of friendship and created a family with intellectual, artistic and political connections.

During the first lockdown, just after my nomination for the French Pavilion, I watched many films – focusing mainly on French and Italian co-productions with Algeria. Since I am French and Algerian, making work for the French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, I decided to concentrate on these three countries where film production was important. I pulled out scenes from each of the films to re-create, to make remakes. My new project is also an homage to The Battle of Algiers (1966), directed by Pontecorvo, which won the Golden Lion at that year’s Venice Film Festival. I wanted to re-enact the community and family spirit that united these productions. I invited my parents and my son, as well as friends, and the curators of the French Pavilion – Sam Bardaouil, Till Fellrath and Yasmina Reggad – to participate in my film. You might recognize a few artists, too. Many of the cast are not professional actors. It is a clin d’oeil [nod] to The Battle of Algiers and other films from that generation using similar approaches. Some of the film crew are also included in the project. This is a film about films and filmmaking. Since my work tends to be autobiographical, it made sense to include friends, family and colleagues. I am also hoping to restore the idea of community and alliances mentioned earlier. I was born in France in 1963, one year after Algeria won its independence, and grew up in Paris, so you can imagine the racism I experienced at that time. All of that is included in this project, because I’m a product of that legacy.

RT I was thinking about your work within the broader context of archival films from North Africa, such as Fatma 75 [1975], in which the director, Selma Baccar, also re-enacts scenes from history. Or, more recently, Bouchra Khalili’s Foreign Office [2015], which again uses re-enactment to focus on the transnational solidarity movements in Algiers.

ZS This film is not just about re-enactment of a formal aesthetic of the 1960s and ’70s. It uses the processes of the mise-en-abyme through costume, props and set design. Voice-overs – usually by men – were another common feature of Third Worldist cinema, so I am using my own voice to narrate personal stories.

RT Your point about narration reminds me of the cult Algerian film Omar Gatlato [1976], directed by Merzak Allouache, which looks at the role of men in Algerian society through the character of Gatlato, around whose voice-over the film centres.

ZS You are right. For me, in Omar Gatlato, the voice-over is the film. This is a strategy often used in films of the 1960s and ’70s. We can see it in the French cinéma vérité, where protagonists often were asked to break the fourth wall, to talk to the camera. In my film, I also weave behind-the-scenes moments into more conventional shots.

Another aspect of my project, which takes place beyond the walls of the French pavilion, is the restoration of a film called Les Mains Libres [Free Hands, 1964], which was presumed lost almost from the date of its creation. The film, which was Algiers’s first international co-production, was entirely financed by Casbah Productions, the same company that produced The Battle of Algiers, with an Italian filmmaker called Ennio Lorenzini. Having premiered at Cinema Afrique in Algiers in 1966, and subsequently that same year in a few cities in Italy and France, it then seemingly disappeared from the cinema circuit. I found many related articles about the film in the Cinémathèque Française and Algérienne. Many Algerian film historians have referenced it in their writing without being able to see it. I decided to look for it and I found it in the Audiovisual Archive Foundation of the Labor and Democratic Movement in Rome. I contacted the Cineteca di Bologna to discuss a possible restoration as part of my project and it is now underway. At last, after 56 years, we will be able to circulate the film internationally!

RT There are a lot of Arab revolutionary films in the Italian Communist Party archives that, over the past five years, many of us from the Southwest Asian and North African region have managed to unearth. There are some other interesting restoration and grassroots projects happening in Algeria, currently. One that comes to mind is being spearheaded by Habiba Djahnine, who made a documentary about the assassination of her feminist activist sister, Nabila, in the Algerian city of Tizi Ouzou in 1995 [Letter to My Sister, 2006]. Djahnine set up a collective to produce cinema primarily by Amazigh women – traditionally marginalized because it’s about indigenous life, or because it’s considered to be militant. Have you been operating within those sorts of networks?

ZS The Algiers art and film scene is small, so we all tend to know each other. I’ve known Habiba for a long time and the work she does is amazing because it is about transmission and training for women mainly. I think this type of coaching was missing in Algeria until Habiba created it. The 1960s and ’70s were rich in Algerian cinema. But, in the late 1980s, it went downhill: cultural production died due to the political turmoil Algeria found itself in. In the 2000s, it slowly returned, but funding wasn’t as it had been. Unlike in the 1960s and ’70s, the state interest in cinema production fizzled out. Perhaps it was not deemed a priority anymore.

RT In 2011, you founded aria, an artist residency in Algiers.

ZS Unfortunately, the pandemic has had a significant impact on our involvement and travel to Algeria. However, we have still managed to organize a residency project with Villa Arson in Nice for an Algerian artist. The focus of aria is mainly centred on contemporary art rather than cinema. It is always based on invitations to artists and curators to spend time in Algiers and share locally – via formal talks or informal discussions, portfolio readings or workshops – their art practice and experiences: aria was about knowledge-sharing.

For the biennial, I also decided to create three newspapers ahead of the French Pavilion opening, each focusing on a different city of influence: Algiers, Paris and Venice. I’m asking for contributions in the form of playlists, academic texts, artists’ images or film programmes, all connected to my artistic project for the French Pavilion. These three newspapers will also include some of my archival research otherwise not accessible or on view.

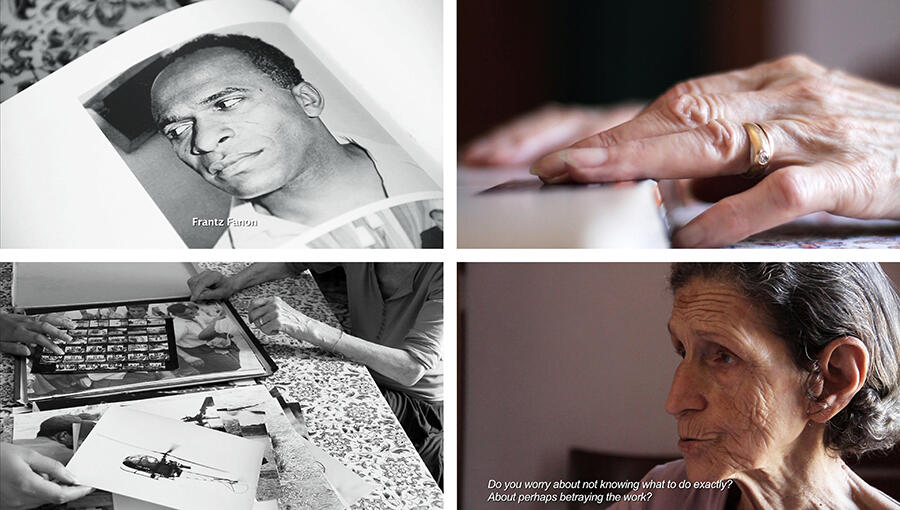

RT Sometimes, photography is the subject of your films – Gardiennes d’images [Image Keepers, 2010], for instance, about the Algerian photographer Mohamed Kouaci. How does photography inform your practice?

ZS For me, analogue photography is an extension of moving-image work, especially when I’m using 16mm or 35mm film. I create both immersive photographic installations and simple, framed images to hang on the wall. However, I do not use film and photography in the same way. For example, in Gardiennes d’images, it was crucial to use video to record the stories that Kouaci’s wife, Safia, told about her late husband. The project is primarily one of storytelling and, within it, I included black and white photographs from Kouaci’s archives, rather than exhibiting them alongside my video installation.

Another example is Saphir [2006], a film I shot in Algiers, where I made a series of photographs connected to, but very different from, the film. They are complementary but they are not a substitute. If the two can be exhibited together, I am happy, but they also operate as stand-alone artworks.

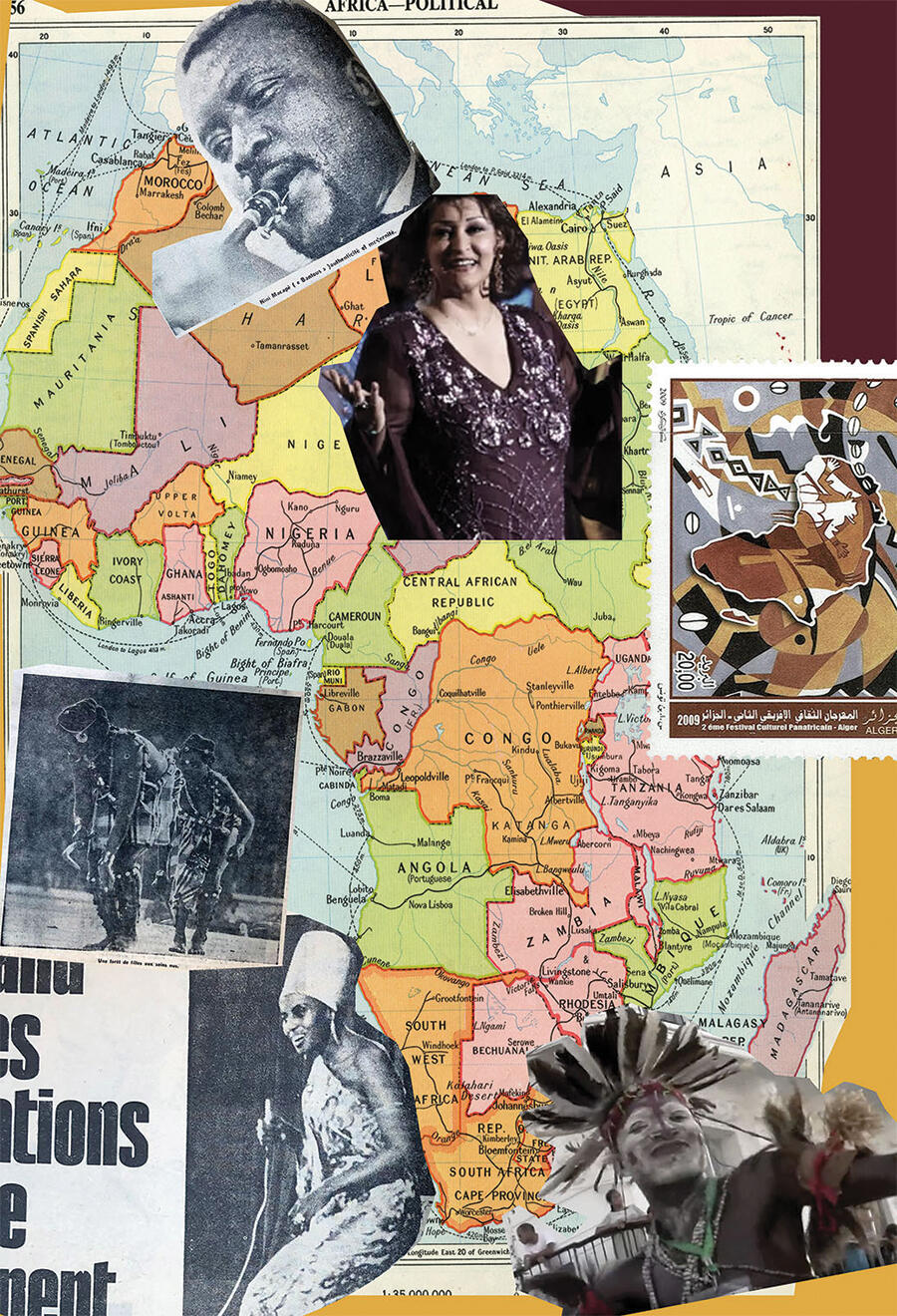

I’m certainly using photography less conventionally than I used to – displaying images in lightboxes or using them in installations – I have grown tired of the standard model of the framed photograph on the wall. In 2019, I presented Way of Life at Jeu de Paume, Paris – an installation in which I re-created my living room in Brixton, London, by covering the gallery walls with photographs of my own walls at home. I was playing with the idea of trompe-l’œil. This was the first time I had made such a large-scale piece, which included my furniture and personal objects. Visitors could sit and chat, listen to music or watch an interview with the curator Nadira Laggoune about the 1969 Algiers Pan-African Festival.

In the same exhibition, I also presented a series of photomontages [For a Brief Moment the World Was on Fire] that incorporated plenty of archival material from my research and findings, which were displayed alongside objects connected to my enquiries. These pictorial presentations were important so I could share my many years of research into Pan Africanism in Algeria. Let’s not forget that only a few academics and artists are able to travel to the country in person, so unearthing documents on the subject can be difficult.

RT Language is a pervasive topic of enquiry throughout your practice. For example, in Mother Tongue [2002], three generations of your family all speak different native languages – Arabic, French and English – meaning your mother and your daughter can’t communicate in the same language. Does Les rêves n’ont pas de titre address any of these same concerns?

ZS Les rêves n’ont pas de titre is about internationalism, so language also has its place. I asked the protagonists to voice their dialogues in their native language or mother tongues: Arabic, Dutch, French, German and Spanish.

RT How do you hope the audience will engage with the work?

ZS My primary hope is that the work will recall and re-enact a fructuous period of artistic, intellectual and political alliance in the domain of culture illustrated by cinema and filmmaking. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement during the first COVID-19 lockdown really moved me. I could not help but think of the 1960s and early ’70s, when people rallied globally to protest war and to promote nuclear disarmament, feminism, the civil-rights movement and anti-imperialism through music, theatre, literature, art and cinema. Whether these protests took place in America, France, the UK or the Global South, they were all extremely important in expressing commonalities of political opinion. The global uprising prompted by the police murder of George Floyd in 2020 showed us that these international impulses and alliances today can be reactivated.

I truly believe we need to go back to those radical political alliances and shared experiences to better move forward. Hence my interest in the archive: to expose, reconsider and challenge history. It is necessary to examine both private and personal archives: there are many of them when you look for them. And let’s hope that some inaccessible state documents will eventually become accessible. I am thinking of French President Emmanuel Macron’s recent authorization to release highly classified information from the country’s national archives about the Algerian war of independence. These documents will shed light on some of the darkest chapters in France’s 20th-century history and will undoubtedly change the official narrative on the colonization of Algeria.

RT As Donna Haraway observed in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene [2016], tension in dialogue is so important – not something to shy away from. What do you personally want to take away from participating in the Venice Biennale?

ZS In the past, some artists might have refused this commission but, for me, it was important to accept it because I’m only the fifth woman, and the first non-white woman, to be invited to represent France at the Venice Biennale. I have many stories to tell, and I intend to share them! The work exhibited won’t be so different from my previous artworks. In fact, it is a continuation of the installation Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go [2019] – my project about the Pan-African Festival of Algiers in 1969. To me, it made sense to push forward my latest work by delving more into the issues associated to that historical context. The Pan-African Festival was created to promote the idea that culture must be the ‘weapon’ used to fight colonization. Being nominated to represent a nation is challenging in itself. My approach was to look beyond one specific country so as to question the very notion of nationhood.

As an artist who likes demanding projects, working on such a large-scale production in such a visible space as the Venice Biennale was an opportunity I could not resist. I also knew that a small number of people would object to a London-based, French-Arab-Berber-Algerian woman representing France! That makes it even more important for me to reaffirm on an international stage my belief in a more inclusive, interrelated and decolonized art world and art histories. My nomination is a major shift in the French contemporary-art landscape and sets a precedent for other artists with a plurality of identities.

Zineb Sedira's solo exhibition is on view at the French Pavilion of the 59th Venice Biennale from 23 April to 27 November 2022.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 226 with the headline ‘Interview: Zineb Sedira’. For additional coverage of the 59th Venice Biennale, see here.

Main image: Zineb Sedira, Les rêves n’ont pas de titre (Dreams Have No Titles), 2022, production still. Courtesy: © Zineb Sedira/DACS, London, and kamel mennour, Paris; photograph: Thierry Bal