What Happened to the Women Artists who Won Prizes in 1918?

‘Prize & Prejudice’ at London's UCL Art Museum is a bittersweet celebration of female talent

‘Prize & Prejudice’ at London's UCL Art Museum is a bittersweet celebration of female talent

At the UCL Art Museum’s exhibition ‘Prize & Prejudice’ I find myself engaged in a game of speculation. What happened to the women who studied at the UCL Slade School of Fine Art 100 years ago, whose student work is hung on the walls and propped on easels? What did they make when they left, and what would they have made, had they lived in a society amenable to the careers of female artists? Since 1897 the museum has collected artworks produced by the recipients of the Slade’s numerous annual student prizes. To coincide with the centenary of the Representation of the People Act – the first time (some) women were permitted to vote in the UK – ‘Prize & Prejudice’ sheds light on the work of women included in this historical collection, focusing on the class of 1918 and other notable contributions from the era. The resulting exhibition is bittersweet: at once a celebration of female talent, an insight into life at art school at a momentous time in British history and a reminder of how much potential may have gone unfulfilled as a result of gender inequality.

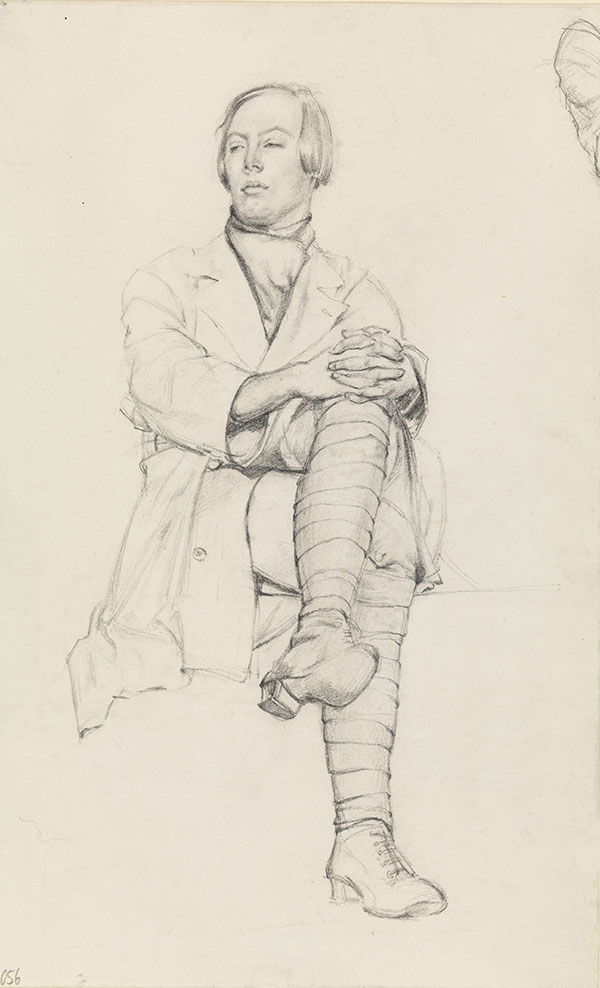

The majority of those awarded for their early promise have subsequently faded from view. Take Mabel Greenberg, who won first prize in 1918’s ‘Head Drawing’ category (commonly known as portrait drawing). Her Study of a Young Man (1918) is a wonderfully characterful pencil drawing of a youth wearing plus fours and the sort of caddish sneer that could put Casanova in the shade. The curators hypothesize that Greenberg may have gone on to become a portrait artist, a familiar hustle for art school graduates, but little is known of her until her death in 1933 aged 43.

A question mark also hangs over the fate of Alice Joyce Smith. Born in Hackney, her father worked in the scavenging trade and when he died, her mother took a job attending lavatories. Smith was prodigious at the Slade, winning four prizes in 1918 alone – including for her fine pencil drawing Standing Female Nude (1918) – but after that the trail runs cold. What became of her? It is tempting to fantasize about a stash of hidden artworks waiting to be discovered and perhaps one will be. But art history is riddled with the myths of genius that prevails in the face of hardship and they tend to paper over the cracks of the structural inequalities that have held myriad women back, particularly those from working class backgrounds.

1918 was undoubtedly an extraordinary time to be an art student. World War One ended, the suffrage movement finally bore fruit and, owing to the slaughter of 700,000 British soldiers and the continuation of conscription after the armistice, only 16 of the 119 students enrolled at the Slade were men. Under the tutelage of the newly appointed Professor Henry Tonks, whose studies of the facial disfigurements of servicemen are a testament to the butchery of war, modernism was creeping into the classroom. The Victorian academy model of art education – copying plaster casts and drawing life models draped in decorously placed fabrics – was still in operation. But it was mingling with developments on the continent and a social consciousness ushered in by the bloodiest conflict on record.

Two artists for whom neo-classicism and modernism come together to startling effect are Winifred Knights and Antonia Violet Hamilton Bradshaw. In Knights’s tempera painting A Scene in a Village Street with Mill-Hands Conversing (1919) – joint-winner of the ‘Summer Composition Prize’ of 1919 – ashen-faced workers converge in a town square against a backdrop of farmland and factories. The composition combines the Quattrocento style of early Renaissance painters such as Sandro Botticelli, the mechanical angularity of cubism and the bleakness of social realism. Two years prior to making the work, Knights witnessed a deadly explosion at a munitions factory in Silvertown, London. The accident affected her profoundly and lends some insight into her epic, funereal style.

Knights went on to win the prestigious Rome Scholarship in 1920. In 2016, almost 70 years after her death, she was the subject of her first major retrospective, ‘Winifred Knights (1899–1947)’, at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery. Far less is known of Bradshaw, who left the Slade in 1916. In her oil painting The Flight into Egypt (1915), the biblical tale of the escape from King Herod’s baby-killing edict is given the full period treatment. Mary is dressed for the desert like an English lady awaiting afternoon tea, in a cream cape, green blouse and blue bead necklace. Joseph is done up like one of Paul Cézanne’s card players, in a tall brimmed hat and labourer’s jacket.

In recent history, the phrase ‘overlooked woman artist’ has entered popular parlance. But what, precisely, does it mean? In her 1971 essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, the late art historian Linda Nochlin argues that it is misleading to assume that women have simply been robbed of the limelight. ‘The arts,’ she writes, ‘as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive, and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male.’ The problem runs deeper, and cannot always be rectified by paying overdue attention. For every Winifred Knights, there are countless talented women – some of their work displayed in this exhibition – who did not get the chance to develop their practices after graduating.

‘Prize & Prejudice’ offers a valuable lesson. As the recent study‘Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries’ led by sociologists from the Universities of Edinburgh and Sheffield shows, unpaid and nominally paid labour practices are pervasive in the cultural sector and class, ethnic, and gender biases continue to prove prohibitive. The restoration of neglected legacies is crucial and illuminating work. But when it comes to building an egalitarian art world, visibility is secondary to the provision of opportunity, funding, and support. Without this, any artist – no matter how talented – will struggle to flourish.

‘Prize & Prejudice: A selection of works from the Slade class of 1918’ runs at the UCL Art Museum until 8 June (with restricted opening times). UCL Art Museum is part of UCL Culture

Main image: Gwen John, Studies after Michelangelo (detail), 1897 –1898, red chalk and pen and black in over black chalk on stout wove paper. Courtesy: UCL Art Museum